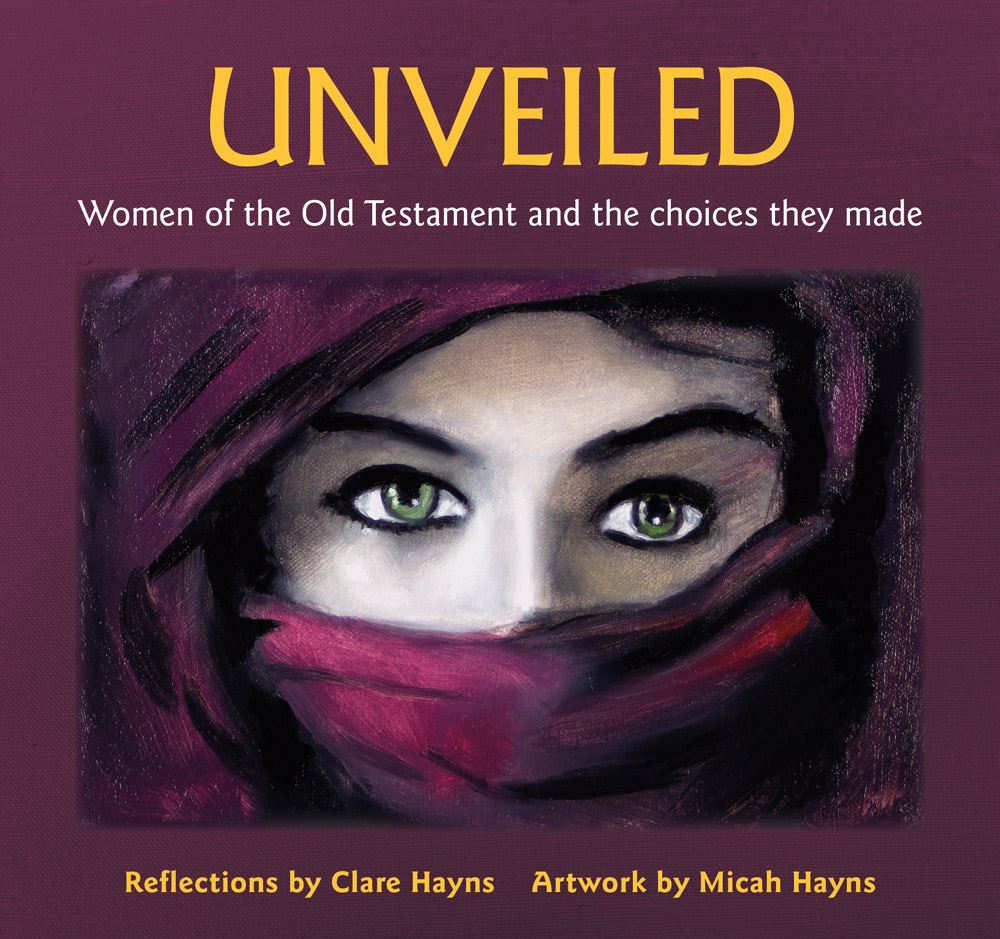

In the last of our articles inspired by Clare and Micah Hayns’ best-selling book Unveiled: Women of the Old Testament and the choices they made, Baptist theologian Helen Paynter finds echoes of today’s women’s bravery in the courage of their Old Testament sisters.

3 July 2022

Courage in the face of violence and threat

Standing up to a powerful man comes at considerable cost.

Unveiled, p. 177

In 2017, the #MeToo tag went viral, becoming a global phenomenon within a matter of weeks, and emboldening millions of women – and also men – to name their experience of sexual harassment and abuse. What had, in many places, been a shadowy secret was brought into the light. The scale of the pandemic of abuse became clearer to many. Systems and structures that collude to silence women were brought under scrutiny. Serial abusers who had concealed their crimes with threats, non-disclosure agreements and the ‘old boys’ network’ were exposed and brought to justice.

What few people might imagine is that the women who shouted ‘Me too!’ had sisters who had gone before them and had left their traces in the pages of the Old Testament.

The Old Testament has a surprising collection of stories about women who stood up to powerful men, some of whom feature in the beautiful book Unveiled by Clare and Micah Haynes. Not all were speaking up about sexual abuse per se, but they share other common features: boldness, courage and truth-telling in the face of violence or threat.

‘The women who shouted “Me too!” had sisters who had gone before them.’

Old Testament sisters

We might think of the two different Old Testament women named Tamar. The first Tamar’s story is told in Genesis and features in Unveiled. The second Tamar’s shocking story is recounted in book of Samuel. The daughter of King David, she appeals to her lecherous half-brother with remarkable courage and wisdom. ‘No, my brother, do not force me… do not do anything so vile… you would be as one of the scoundrels in Israel’ (2 Samuel 13:12–13). Tragically, Tamar’s entreaty is over-ridden by her rapist, but when she is thrust out from his room afterwards, she raises the outcry, which is the traditional appeal for justice. ‘Tamar put ashes on her head, and tore the long robe that she was wearing; she put her hand on her head, and went away, crying aloud as she went’ (v. 19).

Or we might turn the pages to read of Rizpah, whose two sons were brutally murdered, on King David’s orders, in retribution for a crime their father Saul had committed. To compound this villainy, David allowed their bodies to remain exposed on the hillside for months, a dreadful act in the ancient world. In the face of such injustice, Rizpah, like Tamar, protested vigorously, making a public nuisance of herself as she guarded her sons’ bodies and grieved for them (2 Samuel 21:10). Such actions were dangerous under despotic kings who could easily have their thugs knife you (as one example among many, see 2 Samuel 20:8–10).

‘In the face of injustice, Rizpah protested vigorously.’

Or we could thumb further through our Bibles to read of another despotic king. In the book of Esther we read the story of Vashti, who boldly refused to be objectified by her husband at his debauched party.

Each of these women creatively and boldly called out the violence of a powerful man. They were noisy, stubborn and caused a public nuisance.

But not everyone was able to do that – then, as today. In Judges 19 we read of the horrific gang rape and murder of a secondary wife, thrust into the hands of a mob to protect her husband. She has no voice, her protest is stifled and she does not survive to raise the outcry. And though the act precipitates civil war in Israel, many more women were raped as a direct consequence of that military action, suggesting that the chief motivation was wounded male pride rather than outrage about a woman’s violation.

And so it falls to her sisters to take up her cause. To name the abuse, to call out the abuser, to cry for justice and safety.

In modern times many women have taken up the story of that nameless woman: Bekah Legg of the domestic abuse charity Restored, and biblical scholars Phyllis Trible, Isabelle Hamley and myself, to name just four. I am reminded of what took place after the murder of Sarah Everard: the protests on Clapham Common and the Reclaim These Streets movement, which employed public grief to make a wider claim for justice.

‘They were noisy, stubborn and caused a public nuisance.’

Sadly, I can’t think of any good examples in the Old Testament narrative where a man takes up a woman’s cause or speaks effectively on her behalf. But if we keep turning the pages, we will eventually encounter a man who does, and repeatedly. A man who publicly defends a woman whose ‘great sin’ (probably sexual) has been forgiven, and whose gratitude leads her to weep over his feet and anoint them with oil (Luke 7:36-50). We can just imagine the sniggering and lewd remarks that were probably rippling through the onlookers as she did so. Jesus sternly rebukes them.

This is the same man who refuses to join the crowd in baying for the blood of a woman caught in the act of adultery, the crowd that was desperate to vilify the woman while curiously indifferent to the man she was with. Jesus shames the crowd into leaving, and then sends her home with gentle words.

Brothers, be more like Jesus

Because I have written about domestic abuse, I find myself invited to speak on the subject from time to time. When the audience is free to choose whether to attend (unlike, for example, when I speak to trainee ministers or priests), it is always predominantly women who attend, usually outnumbering men by around seven to one. Why are men not more interested in this matter? (There are, of course honourable exceptions, such as this.)

Brothers, be more like Jesus, I implore you. Speak out against injustice. Actively stand against abuse. There is so much hatred and harm out there that it requires more than just passive non-complicity.

But the fact that these stories are present in our Bibles should encourage us. The accounts of these ancient women and the things they suffered have not disappeared in the patriarchal sands of time. These women mattered to God, and so he ensured that their stories were preserved in his word. And so they should matter to us, too – they and those who suffer like them in our own day.

‘There is so much hatred and harm out there that it requires more than just passive non-complicity.’

These stories should encourage contemporary sufferers of abuse to believe that God cares, and maybe to embolden them to speak out. It is much harder for abuse to thrive when it is brought out of the shadows into the light; when it can no longer hide behind threats, non-disclosure agreements and the old boys’ network.

But, rest assured, in the end all will be revealed:

Nothing is covered up that will not be uncovered, and nothing secret that will not become known. Therefore whatever you have said in the dark will be heard in the light, and what you have whispered behind closed doors will be proclaimed from the housetops.

Luke 12:2–3

Because, as the psalmist reminds us:

He who planted the ear, does he not hear?

Psalm 94:9

He who formed the eye, does he not see?

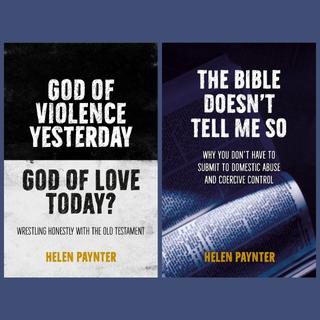

Following a career in medicine, Helen Paynter is now a Baptist minister and the director of the Centre for the Study of Bible and Violence at Bristol Baptist College. She is the author of two BRF books…

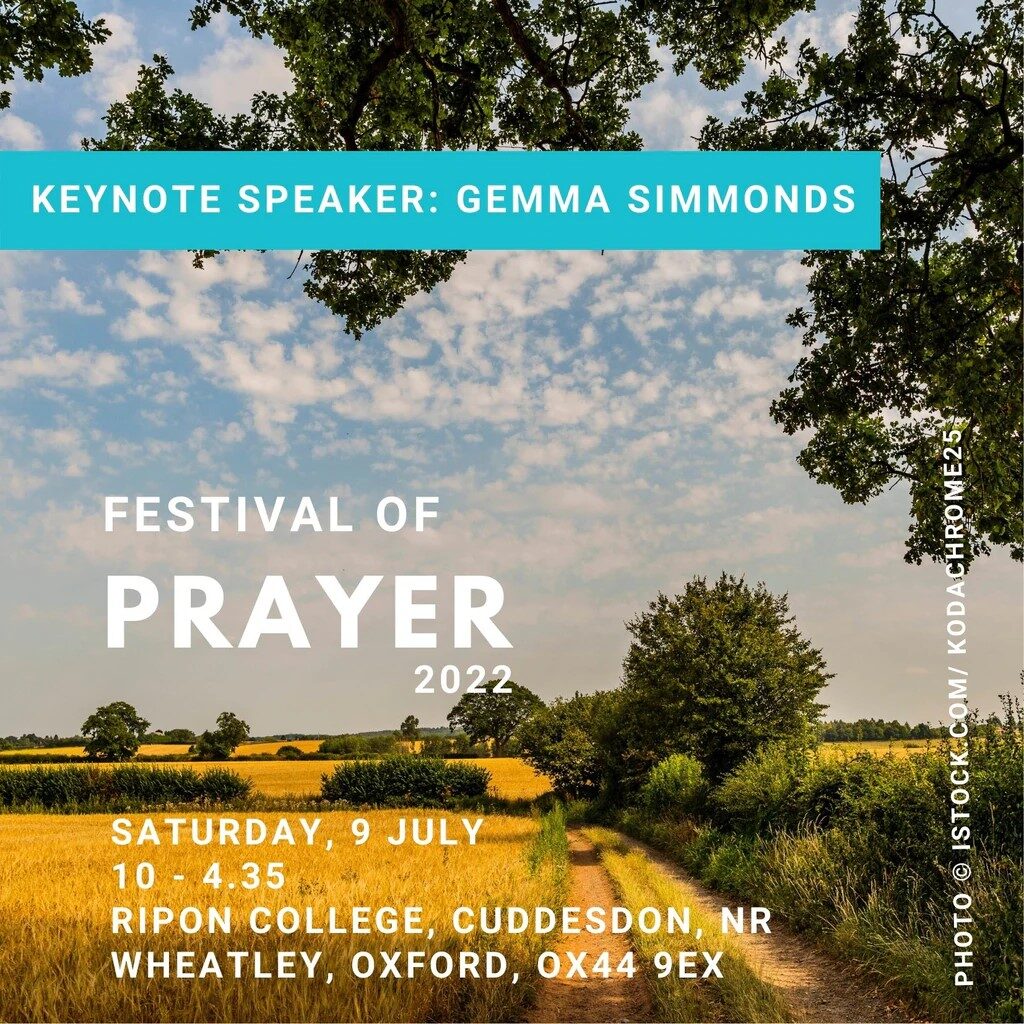

Festival of Prayer '22

Prayer and personality

After a two-year absence, the Festival of Prayer returns on Saturday to the delightful setting of Ripon College in the picturesque Oxfordshire village of Cuddesdon. The festival is an opportunity to invest in your relationship with God, in the company of deeply thoughtful and experienced speakers.

Written with frankness and humour and illustrated with striking artwork from a young Oxford-based artist, Unveiled explores the stories of 40 women in 40 days. Each reflection ends with a short application to everyday life, guidance for further thought and a prayer.

In addition to the book, in a first for BRF, digital marketing officer Iris Jenkins and videographer Adrian Serecut, have produced a series of eight stunning videos exploring some of the women’s stories. The videos are all available to view now, without charge, and come with additional downloadable material, including questions for group discussion or individual reflection.

Scripture quotations are taken from The New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, Anglicised edition, copyright © 1989, 1995 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.