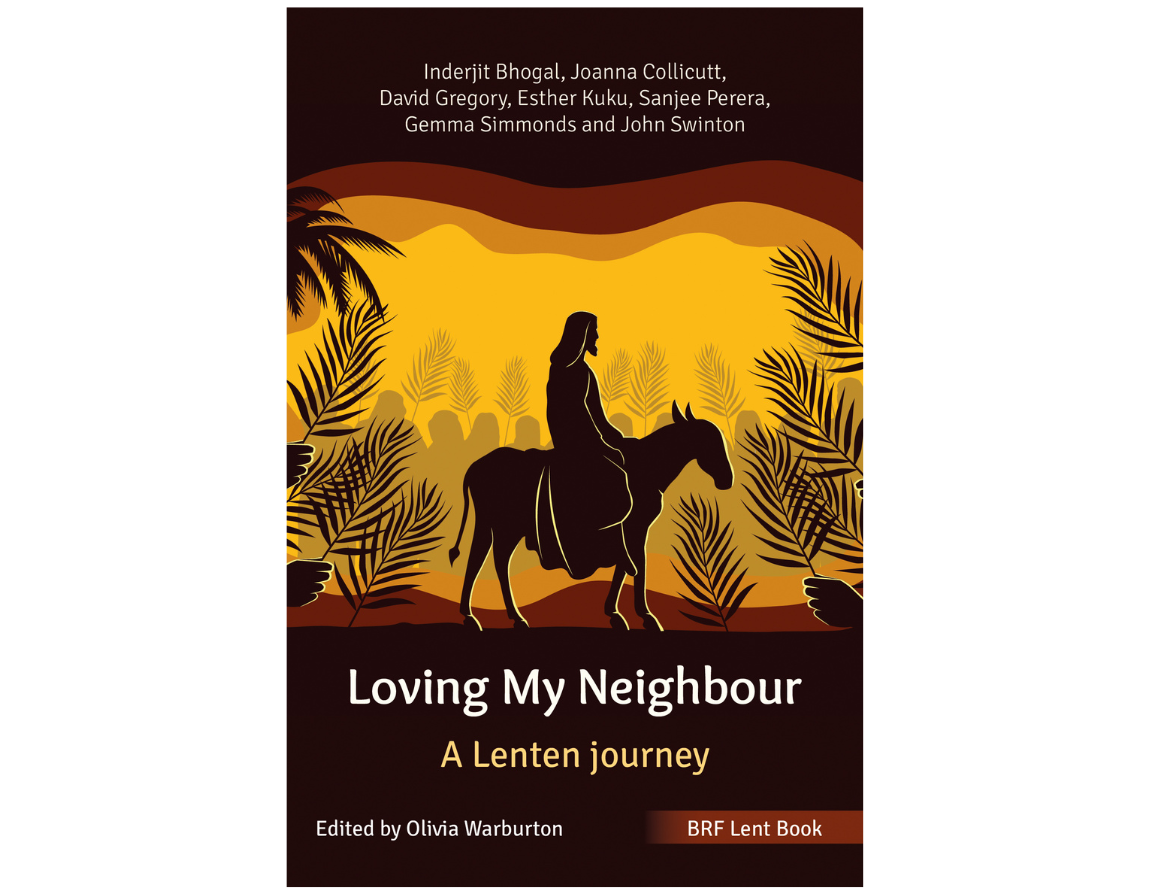

Our 2024 Lent book Loving My Neighbour focuses right to the heart of discipleship and what living out our faith really looks like. Bringing together well-respected voices from across the church, it offers a broad and diverse range of perspectives on the biblical imperative to love our neighbour, and provides thoughtful encouragement as we seek to live this out in today’s context, through Lent and beyond. Joanna Collicutt has written this article based on her reflections on ‘loving to the end’.

24 March 2024

To teach his brethren

We are sometimes so focused on the theological significance of Jesus’ death – his work of salvation for the whole world – that we fail to notice the more human gift that he offered us: he showed us how to die well. Yet it is a lesson we all need to learn.

The medieval German theologian and mystic Meister Eckhart wrote that Christians need to be taught ‘the art of living and dying’. They need to be taught this art not just by instruction but to see it personally embodied in a life well-lived. Furthermore, as that life moves into a phase increasingly dominated by limitations, frustrations, losses and pain, people need to see that this can be navigated well and with integrity.

In his famous hymn ‘Praise to the holiest in the height’, John Henry Newman explains that Jesus did exactly this:

And in the garden secretly,

and on the cross on high,

should teach his brethren, and inspire

to suffer and to die.

So, what can we learn from Jesus’ preparation for his own death? Here are some principles.

Meister Eckhart wrote that Christians need to be taught ‘the art of living and dying’, not just by instruction but to see it personally embodied in a life well-lived.

Left: Sculpture of Meister Eckhart (left) and John I, Duke of Brabant (right) at Town Hall Tower, Cologne by Elisabeth Perger (b. 1960) © Raimond Spekking / CC BY-SA 4.0 (via Wikimedia Commons); cropped

Facing not seeking

Jesus faced up to his death and spent a good deal of time trying to prepare his disciples for its reality. They resisted this reality (Matthew 16:21–26), but Luke tells us that Jesus was resolute and readied himself to the challenge (Luke 9:51; 13:33).

Yet Jesus did not seek death for its own sake. For a time he was careful to avoid arrest in Jerusalem by using safe houses, but when he understood that his hour had come he went out to meet his foes (John 13:31). Even then, the gospel writers are at pains to make it clear that death was the last thing Jesus wanted. If he could have avoided it, he would have (Matthew 26:39 and parallels). He loved life, and he understood the horror of death.

Comfort and provision for those left behind

Part of Jesus’ facing of his death was the care he gave to those he would be leaving behind. John 13—16 is an extended farewell in which Jesus expresses his love and intimacy with his followers. He models the way of life they are to embrace in mutual love and service, offers them an image of attachment in the discourse on the true vine, and promises them the Spirit to comfort them in their loss. In the synoptic gospels, Jesus offers the breaking of bread as a way both to remember him and to re-member themselves as a body (Luke 22:19).

Part of Jesus’ facing of his death was the care he gave to those he would be leaving behind.

Receiving care with good grace

Throughout his life Jesus entrusted himself to others: to Mary and Joseph through his childhood; to the seamanship of the disciples to escape from the crush of the crowds (Mark 3:9); to the female followers who provided for him (Luke 8:2–3) and the hospitality of those who opened their homes to him (Luke10:38); to the goodwill of the Samaritan to give him a drink of water from the well (John 4:6–7).

As his death approached, he praised a woman (probably Mary of Bethany) for recognising it and anointing his body for burial (Matthew 26:12; John 12:7), describing her action as beautiful or fitting. Later, in Gethsemane he seemed genuinely to desire the presence of his disciples to uphold him in prayer and comfort him by their solidarity.

So, to follow Jesus is to face up to the prospect of our own death, to make provision for those left behind, and to learn to receive the care and support of others with grace and joy.

And what does it mean to follow Jesus in his undergoing of death?

In a theological sense Jesus death might be seen as heroic, but in a human sense it was full of pathos – literally ‘pathetic’ – and this is also recognised theologically in the image of Jesus as a lamb who was slain. Jesus wept not just in empathy with others, but also at his own fate that was the natural consequence of his rejection by those he loved (Luke 19:41). The writer to the Hebrews says that Jesus cried in Gethsemane (Hebrews 5:7) in his anguished struggle of discernment. And, of course, he cried out to his Father on the cross (Matthew 27:46).

To follow Jesus is to face up to the prospect of our own death, to make provision for those left behind, and to learn to receive the care and support of others with grace and joy.

Left: Stone relief of the agony in the garden of Gethsemane. Photo © Fallaner / CC BY-SA 4.0 (via Wikimedia Commons); cropped

Jesus has faced all that we fear

When the time was right Jesus moved from active ministry into his ‘passion’, a period in which he was entirely passive, treated as an object, and – in human terms – without agency (Matthew 27:42). He underwent an agonising physical process in which, among other things, he became dehydrated (John 19:28). He has faced all the things that horrify us about death.

Jesus’ death was thus an ordinary human death, undergone extraordinarily well, authentic and exemplary. Yet much more was going on. Jesus, the craftsman, was doing something creative; Jesus, the divine Saviour, was transforming death itself. This is hinted at in his cry to his Father, framed in the opening words of Psalm 22, a psalm that journeys through deep darkness and suffering into a transformed sense of God’s goodness and sovereignty. Even as he hung on the cross he made space to re-member the human lives of his mother, the beloved disciple, and a convicted criminal who hung alongside him.

Creation and re-creation

Jesus’ death was uniquely sacrificial in the sense that it was life-giving for all humanity. He understood it to be the culmination of his mission (John 19:30). But he also said that this was in some sense the calling of us all. He reflected that a grain of wheat falls into the earth in order to bear much fruit (John 12:24). Death and dying are seen to be about creation and re-creation. As followers of Jesus, we join in that creative and life-giving work through lives marked by sacrifice and praise, and through it we participate in his glorious resurrection.

To sum up: to follow Jesus is to approach our living and dying as creative acts that bring fullness of life to ourselves and others, to be aware of the time when possessions, agency, and treasured relationships are to be let go, and to trust to the ultimate goodness of God. Our deaths do not need to be heroic; we do not need to be strong; we can cry out to God in pain and distress; and we can be sure that he is with us.