Our 2024 Lent book Loving My Neighbour focuses right to the heart of discipleship and what living out our faith really looks like. Bringing together well-respected voices from across the church, it offers a broad and diverse range of perspectives on the biblical imperative to love our neighbour, and provides thoughtful encouragement as we seek to live this out in today’s context, through Lent and beyond. This next extract in our series is from Inderjit Bhogal’s reflections on ‘Loving those who are different’.

10 March 2024

Also love the stranger

The Bible contains the command to ‘love your neighbour, as yourself’. Jesus based his parable of the good Samaritan on these words (Luke 10:25–37). Yet this commandment is stated only once in the Hebrew scriptures (Leviticus 19:18). Around 40 times, in different terms, the Hebrew scriptures hold up the challenge to also ‘love the stranger’. There is no other ethical requirement repeated so often.

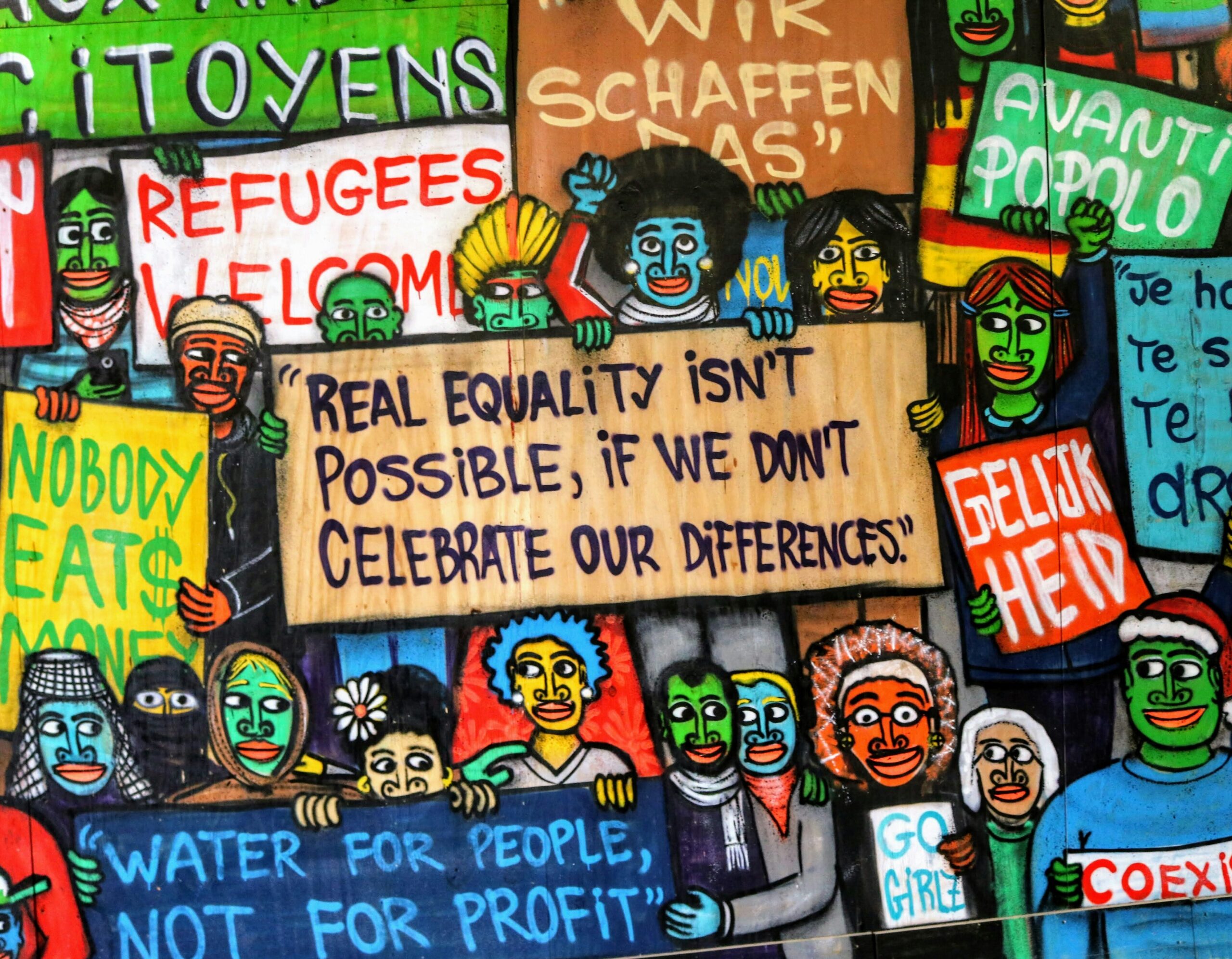

A neighbour is someone a bit like yourself; a stranger is someone who is different. God calls everyone to ‘also love the stranger’, with a hunger for justice.

‘Love the stranger’: there is no other ethical requirement repeated so often.

Left: detail of a folio from the 6th-century Rossano Gospels, depicting the parable of the good Samaritan.

Jesus and the Greeks

Now among those who went up to worship at the festival were some Greeks. They came to Philip, who was from Bethsaida in Galilee, and said to him, ‘Sir, we wish to see Jesus.’ Philip went and told Andrew; then Andrew and Philip went and told Jesus. Jesus answered them, ‘The hour has come for the Son of Man to be glorified. Very truly, I tell you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains just a single grain, but if it dies it bears much fruit. Those who love their life lose it, and those who hate their life in this world will keep it for eternal life. Whoever serves me must follow me, and where I am, there will my servant be also. Whoever serves me, the Father will honour.’

John 12:20–26 (NRSV)

We read in John 12:12–19 that the great crowd at the festival heard that Jesus was coming to Jerusalem and gave him a celebrity reception, welcoming him as ‘the King of Israel’. They are awe-inspired by the raising of Lazarus. Jesus’ opponents are troubled, left exasperated. Pressure has steadily built up around Jesus with plots to assassinate him. The scene is one of intense danger, and one of Jesus’ strategies is to regularly take time out and withdraw from public view (see 6:15; 8:59; 12:36).

Within this context, with all the dangers surrounding Jesus, it appears the whole world has gone after him. This is seen in the fact that some Greeks want an audience with Jesus. They single out Philip to put their request that they ‘wish to see Jesus’ (v. 21). The response of the world is focused in the Greeks. The most important aspect of the mention of the Greeks here appears to be that they are different, symbols of the universal appeal of Jesus.

The only detail we are given is that they made their first attempts to get close to Jesus by linking in through other Greeks. Philip is a Greek name. He plays no part in the gospels outside John, but is noted as the one who preaches in Samaria (Acts 8:5) and who engages with an Ethiopian (Acts 8:26–28). Philip is usually mentioned in John alongside Andrew, who also has a Greek name. There is a Greek bond. Commonalities bring people together.

The image of growth emerging from death is a lesson from nature – the wisdom is that if you resist newcomers and those who are different, the participation of others, the reward of growth in community will be lost.

Embracing difference

Philip and Andrew respond together in the story about bread in the wilderness (John 6:5–8) and here, in bringing the Greek enquirers to Jesus. The followers of Jesus, as represented in the gospel according to John, appear to be making attempts to bring together those of Jewish and other backgrounds, such as Greeks. There are efforts to hold people of different backgrounds together in the earliest expressions of church.

But how are the Greeks to integrate into an existing set of disciples and followers of Jesus? How are they to become part of the earliest manifestation of church? One clue lies in the words attributed to Jesus following the introduction of the Greeks. In our reading, the Greeks don’t get their audience with Jesus, but their presence and request sparks off an important discussion. Jesus’ first words go straight to ‘the hour’, a reference throughout John to Jesus’ crucifixion, the axis on which the universal appeal of Jesus turns in this gospel.

Only a seed that dies bears fruit and reaps a harvest. This is not only a reference to Jesus’ own coming execution, but also to the way Jesus’ community will grow. This is further emphasised in the words, ‘And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all people to myself’, with the editorial comment that ‘he said this to indicate the kind of death he was to die’ (vv. 32–33).

The image of growth emerging from death is a lesson from nature. It is a general rule for all life, individually and communally. In the context of the integration of Greeks into the community, the wisdom is that if you resist newcomers and those who are different, the participation of others, the reward of growth in community will be lost.

Jesus is effectively saying: if you want to grow, individually and communally, don’t cling to yourself and your kind only. Find ways to include those who are different.

Essential to growth

The simple reference to Greeks wishing to see Jesus is a window of insight into the life of the earliest Christian communities; their attempts at how to ‘draw all people’ into their life, and the recognition that including those who are different is essential to growth.

Including those who are different requires sensitivity to the fact that different people have different experiences of God and different interpretations of what God says. Some will interpret the voice of God one way, and others will hear it in other ways, as we together attempt to discern the word and way and will of God (vv. 29–30).

Jesus’ prayer that ‘they may be one’ (John 17:11) is not a plea for good ecumenical relationships, important as they are. Rather, it is a prayer for good relationships and communion in a diverse set of people who come together in his name. The prayer also acknowledges this is essential, though not easy.

Modelling Christ

The importance of making room for people of different backgrounds has been a reality throughout church history and is a critical matter in contemporary church life in all denominations. It is natural, like the Greeks in our reading today, for people to begin their journey to inclusion by linking up initially with those like them. Congregations have to consider which traditional ways of being have to be allowed to ‘die’ in order for new inclusive community to grow and bear fruit.

In fact, facilitating integration is a service. Such service models Christ, and is rewarded with ‘honour’ (v. 26). Jesus is effectively saying: if you want to grow, individually and communally, don’t cling to yourself and your kind only. Find ways to include those who are different.