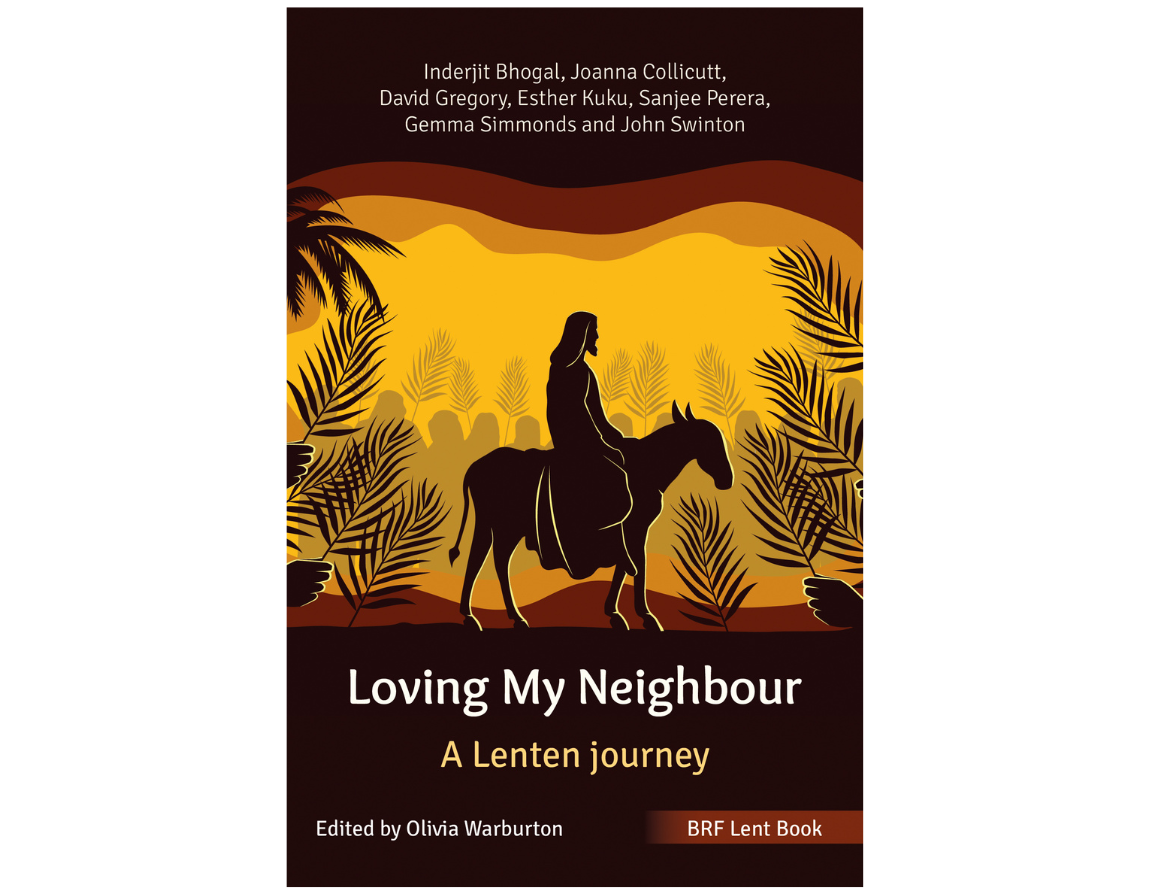

Our 2024 Lent book Loving My Neighbour focuses right to the heart of discipleship and what living out our faith really looks like. Bringing together well-respected voices from across the church, it offers a broad and diverse range of perspectives on the biblical imperative to love our neighbour, and provides thoughtful encouragement as we seek to live this out in today’s context, through Lent and beyond. This next extract in our series is from Gemma Simmond’s reflections on ‘Loving oneself’.

3 March 2024

Getting to know me

Jesus taught us to love our neighbour as ourselves. We can’t love our neighbour well if we haven’t first learned to love and accept ourselves as God loves and accepts us. We can’t give what we don’t have. Embracing the truth about ourselves leads to the humility of knowing that we aren’t the centre of the universe. Paradoxically, this gives us the freedom to be our truest selves, recognising ourselves as the loved and forgiven sinners that God knows and loves.

However unworthy we may appear to ourselves, if we trust in God’s love offered to us without condition, we will learn to have the same confidence that filled Mary of Nazareth as she sang triumphantly of God’s saving power, shining through her human weakness. Knowing ourselves comes from our willingness to be known by God. That may be a challenging thought, but it’s one that helps us to come closer to the God who knows us by name and loves our every molecule.

O Lord, you search me and you know me.

You know my resting and my rising,

you discern my purpose from afar.

You mark when I walk or lie down,

all my ways lie open to you.Before ever a word is on my tongue

you know it, O Lord, through and through.

Behind and before you besiege me,

your hand ever laid upon me.

Too wonderful for me, this knowledge,

too high, beyond my reach.Psalm 139:1–6 (The Abbey Psalms and Canticles)

We can’t love our neighbour well if we haven’t first learned to love and accept ourselves as God loves and accepts us.

Warts and all

Oliver Cromwell was no oil painting, as attested by his portraits. He was undistinguished-looking and afflicted by warts. When a painter, seeking to please him, painted him minus these blemishes, he famously told the flattering artist to paint him as he was, ‘warts and all’.

When we are trying to make a good impression, most of us can manage to put on a good show, at least for a time. But for any intimate relationship to work, we have to dare to let ourselves be known as we are, including in our less attractive aspects. We can’t hide the banal and boring parts of our personality and, sooner or later, we won’t be able to hide our faults and failings. If there is deep trust in the relationship, we won’t be complacent about these things, but we won’t be frightened to be known in our vulnerability either. As countless greeting cards and inspirational posters say: ‘A friend is someone who knows all about you and loves you just the same.’

Yet there is an ambiguity here which we also find in Psalm 139. Knowing someone and being known by them at depth carries both grace and potential threat. Those who lived in eastern-bloc countries during the Soviet era speak of the insidious nature of state terror, where people guarded not only their public words but their private ones as well, and even their thoughts, for fear of being denounced to the authorities by prying neighbours, unsuspected family members turned traitors or the unseen eyes of the secret police. George Orwell’s novel 1984 describes a totalitarian state in which behaviour and even thought are controlled with the slogan ‘Big Brother is watching you’. Is this the kind of God that the psalm is describing, with whom we want to be in intimate relationship?

There is certainly an element of fear and rigid control in the concept of a Divine Watcher, who knows and even anticipates our every move. For most people, the notion of their every word and action, let alone their every emotion and thought, being known before it crosses their own mind is far from consoling. We can (and frequently do) hide our own deepest motives even from ourselves, taking refuge in the opaqueness of our subconscious to avoid being confronted with uncomfortable truths. The thought of God seeing right through us despite our subterfuges can be deeply worrying, and ‘God sees all’ was an admonition frequently used in the past to keep behaviour under control.

The thought of God seeing right through us despite our subterfuges can be deeply worrying.

Knowledge beyond our understanding

Yet the psalm talks of being known through and through as wonderful knowledge, beyond our understanding. St Augustine of Hippo, who certainly did plenty in his young life of which he would later be ashamed, speaks of God being ‘more inward to me than my most inward part and higher than my highest reach’ (Confessions 3.6.11).

Despite his less than blameless life, Augustine finds this thought consoling, because God knows every hidden thought and desire of his, including his desire to be good, even if he can’t accomplish it, and loves and forgives him all the same.

St Ignatius of Loyola, who had studied Augustine thoroughly, bases the first week of his Spiritual Exercises on the same notion. It focuses with ruthless honesty on personal sin and encourages retreatants to make a fearless inventory of their faults, as also encouraged by the twelve steps programme of Alcoholics Anonymous, one of whose founders was a Jesuit priest. The idea behind this is that we can’t experience ourselves as truly forgiven if we don’t experience ourselves as truly known.

Augustine finds this thought consoling: God knows every hidden thought and desire of his, including his desire to be good, even if he can’t accomplish it, and loves and forgives him all the same.

The grace of self-acceptance

Ignatius’ aim was not for us to wallow in self-loathing but to experience the grace of deep, God-given self-acceptance, the same self-acceptance expressed by the reformed slave-trader turned abolitionist John Newton, who wrote ‘Amazing Grace’. He could only experience the sweetness of the sound of amazing grace when he had acknowledged his total dependency on the God who found him when he was lost. God’s ability to find him even in the depths of his own inner darkness was a source of deep and astonished gratitude.

The ambiguity of Psalm 139 is resolved by honesty that leads to gratitude. John’s gospel tells us that ‘the truth will set you free’ (John 8:32). This is the quotation that inspired Sr Helen Prejean, the heroine of the film Dead Man Walking, who spent decades accompanying prisoners on death row to their execution. The film depicts her caught between the horror of the crimes committed and the desire to help the perpetrator face death in hope by telling God, himself and his victims’ families the truth. Being known by God is a risky venture, but only this truth leads to the freedom offered to all through God’s forgiveness.