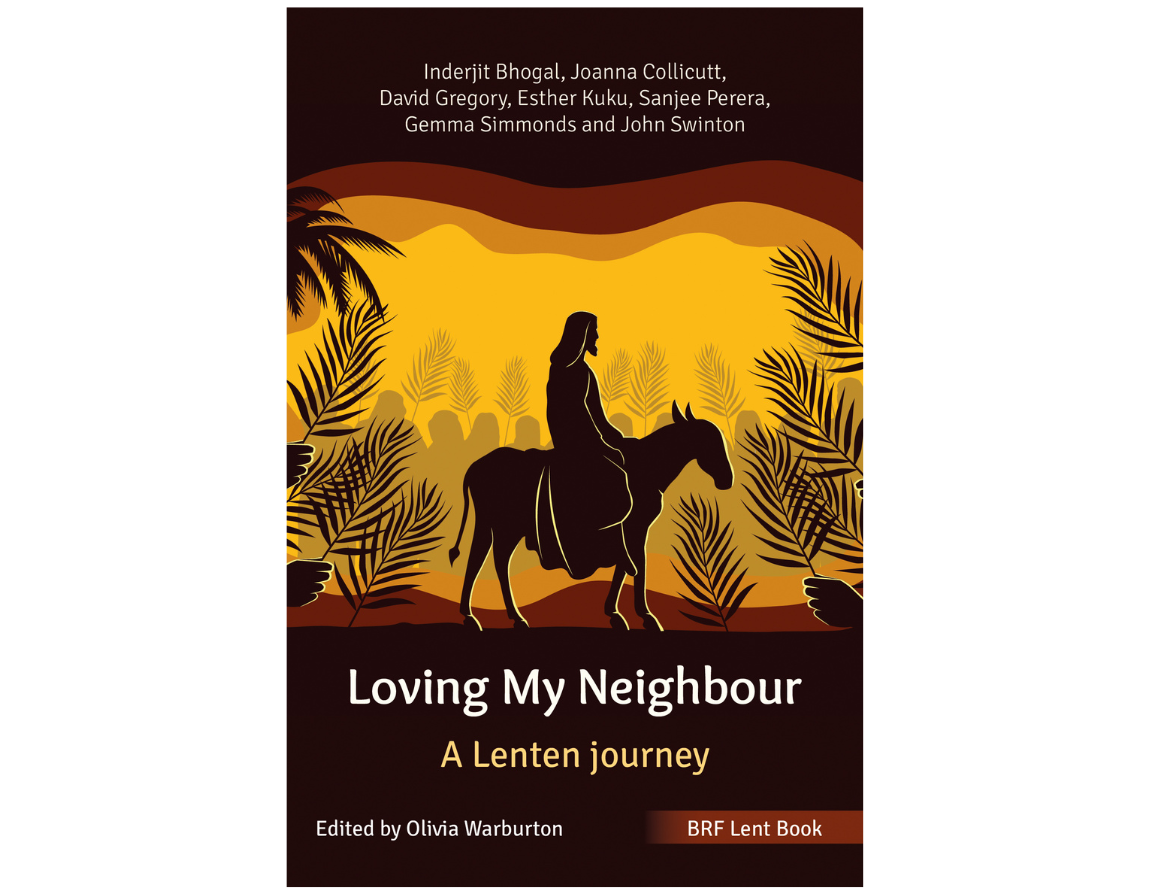

Our 2024 Lent book Loving My Neighbour focuses right to the heart of discipleship and what living out our faith really looks like. Bringing together well-respected voices from across the church, it offers a broad and diverse range of perspectives on the biblical imperative to love our neighbour, and provides thoughtful encouragement as we seek to live this out in today’s context, through Lent and beyond. Looking to Ash Wednesday, Sanjee Perera reflects on ‘Loving in truth’.

11 February 2024

What do we mean by love?

And now these three remain: faith, hope and love. But the greatest of these is love.

1 Corinthians 13:13 (NIV)

The threshold of Lent, when we remember Jesus’ trials as he stormed the courts of justice to determine the cost of love, seems the perfect time to unpack and explore what we mean by love and what it means to love God and our neighbour in truth. To love the other as ourselves, we must first understand the profound truths of who we are and whose image we are made in.

The word ‘love’ is a blunt instrument in the English language. It is a capricious chameleon that confuses most readers, who often struggle to fully understand the finer nuances of scriptural references to love. More than four Hebrew and more than five Greek concepts that encapsulate love are translated as this one multifaceted word in English.

Humankind, full of war, having contaminated a planet, on the verge of crumbling into the sea, trying to climb up on fractured limbs, is held together by a love borne out in Jesus’ 40 days and 40 nights in the wilderness. It is a love conceived in absolute vulnerability and servanthood, and cannot be contained to the frailty of one vessel. It is impossible to love God without loving one’s neighbour. We were created to be a mirror, a simulacrum of a bounty of compassion and generosity beyond our understanding.

Humankind, full of war, having contaminated a planet… is held together by a love borne out in Jesus’ 40 days in the wilderness.

Where are you? What have you done?

Later this week, many of us may attend an Ash Wednesday service where we are marked by a sooty, dust and cinder cross. This cross is meant to represent the burnt ashes of our mortality. It is a mark of penance applied by a priest, often with a reminder: ‘Remember that you are dust and to dust you shall return.’ This sets the tone for Lent as we reflect on what it means to be pilgrims on the narrow way, followers of Christ.

So, Ash Wednesday seems a perfect time to go back to Genesis, to our creation story that roots us in our common humanity, made of star dust and divine breath – dust that made the mostly carbon lifeforms we are. As Carl Sagan said, ‘The nitrogen in our DNA, the calcium in our teeth, the iron in our blood… were made in the interiors of collapsing stars.’ This was kindled into life by a word so potent and creative that the divine breath that awoke us still reverberates through us, and calls to us.

But is this shared humanity and cosmic genesis our core truth? And what does it mean for the way we live in this fallen world on our dying planet, that we were made in the image of love and made stewards of a garden? In Genesis 3:9, when God seeks out his creation, this image bearer of the divine, he calls out in that lush Eden, ‘Where are you?’ Adam replies, ‘I heard you in the garden, and I was afraid because I was naked; so I hid’ (v. 10).

Even then in the grace of Eden, humankind fails to see our kinship to this fount of perfect love, or reveal our naked selves, corrupt and culpable, in the gaze of that perfect glory. This divine question has echoed through the ages: ‘Where are you? What have you done?’ And like Adam, our reaction to the challenge of living and loving in truth is often a weak defensive excuse, founded in fear and self-preservation.

Our common humanity, made of star dust… was kindled into life by a word so potent and creative that the divine breath that awoke us still reverberates through us, and calls to us.

Bound in a selfless love

Recently a newspaper article banner in The Sunday Times read: ‘Our interest counts more than migrant needs.’ It argued that this was about competing human rights, those of citizens and those outside the polis. In Genesis 4:9, the Lord asks Cain, ‘Where is your brother?’ and Cain asks the Lord, ‘Am I my brother’s keeper?’ Our incapacity to love in truth has haunted us from our very genesis. And the Lord reprimands us as he reprimands Cain, ‘What have you done? Listen! Your brother’s blood cries out to me from the ground’ (v. 10).

From the beginning, God has made clear that our lives are bound in a selfless love in servanthood and sacrifice to one another. This is the truth demonstrated by the Trinity: the Father, who sought us out from Eden to Gethsemane, calling for his lost and wounded children; the Son, who emptied himself into the fleshy folds of a virgin’s womb to live in humility, to be reviled and rejected, and to die on the cross; and the Comforter, who is with us, seeking us, calling to us and setting our hearts aflame when we gather in love to seek him.

We live in a world where many don’t believe in a shared humanity, let alone a divine genesis, and submitting to the reflective discipline found in the wilderness of Lent seems an unnecessary exercise. We live in an age where we no longer need to depend on each other, where there is an app for everything and artificial intelligence can manage our needs and comfort. We have Google and Siri to answer life’s big questions and Alexa to locate that cup of sugar we need. Neighbours are prying strangers who are an awkward inconvenience in grating proximity.

We live in an age where we no longer need to depend on each other, where there is an app for everything and artificial intelligence can manage our needs and comfort. We have Google and Siri to answer life’s big questions.

The core truth of our humanity

And yet we live in a world where infants are washed ashore on our beaches and refugees fleeing the shark teeth of danger drown in our cold English Channel. We have learnt to blind ourselves to this world where children go hungry and the vulnerable and elderly die of cold. We live among those forced into modern slavery, and yet look away from the desperation of the abused and destitute. This is alien to the core truth of our humanity that was made to mirror that perfect love, a simulacrum of the divine. And then the salt in the ashen cross reminds us of Jesus’ words in the sermon on the mount:

‘You are the salt of the earth. But if the salt loses its saltiness, how can it be made salty again? It is no longer good for anything, except to be thrown out and trampled underfoot.’

Matthew 5:13

It reminds us that we are called to season the tasteless morsels of life and enrich the banquet. That we are the city on the hill, the light of the world and called to love above all else (John 13:34–35), and this is our simulacrum, our truth, our purpose and our salvation.