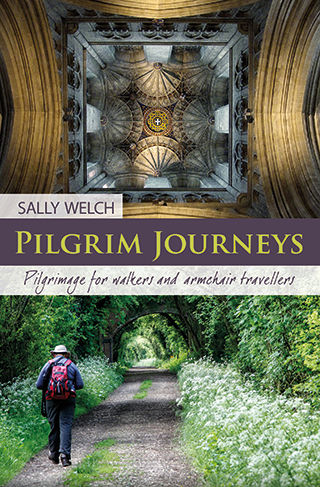

Interest in pilgrimage is booming some 600 years after Chaucer wrote The Canterbury Tales. Traditional routes like the Camino de Santiago are attracting record numbers and new routes are being established throughout the UK and Europe. Sally Welch, BRF author and former editor of New Daylight, is one of the leading voices in the field and has written widely on the subject, including her Pilgrim Journeys for BRF. This is an edited extract.

28 August 2022

Taking the first step

The path stretches out ahead, sunk deep between the hedgerows, which rise to a height of some six or eight feet either side, like green walls, festooned with flowers and plants as if celebrating some perpetual festival. Here and there, a gap in the branches allows a narrow shaft of sunlight to pierce the shade, illuminating a stone or a plant like a spotlight on the carving of an ancient and historic building. Narrow and edged with grass, the honey-coloured stones and mud show evidence of the hundreds of feet that have passed that way, pilgrims following the Way – seeking transformation, enlightenment, peace, God – all sorts of names have been given over the centuries. It is inviting and exciting, beckoning us on to discovery and adventure, encounter and delight; we need simply to take that first step.

Such paths can be found all over the British Isles and Europe, leading through wild countryside and large cities to pilgrimage destinations as famous as Rome or as little-known as Binsey. Pilgrimage destinations such as Iona and Lindisfarne within the UK receive over 150,000 visitors a year, while Santiago de Compostela in Spain numbers its pilgrims in the millions.

‘It is inviting and exciting, beckoning us on to discovery and adventure, encounter and delight; we need simply to take that first step.’

The spirituality of pilgrimage

Bald statistics do not do justice to the growing interest in the spirituality of pilgrimage as something not simply concerned with the journeys of those physically travelling but as a way of living and thinking. True pilgrims do not cease to be pilgrims once the journey is complete: they take the lessons and insights learned from the journey back into their lives at home.

These lessons are often learned through encountering and overcoming the challenges and difficulties of the journey, however long or short it is. They are reinforced by the hours of reflection that are part of the gift of a pilgrimage – time and space to think and reflect, to allow insights to sink deep into heart and mind.

‘True pilgrims do not cease to be pilgrims once the journey is complete: they take the lessons and insights learned from the journey back into their lives at home.’

On the return to everyday life, with its daily routines and obligations, it is easy to forget those lessons, to bury them deep beneath the usual round of work and recreation. How valuable might they be if they were incorporated instead into a pattern of praying and living that could gradually conform the life of the pilgrim to one of constant pilgrimage, sharing the route with others who sought the way of the gospel, looking towards the eternal destination, the heavenly city which is our goal.

The idea of pilgrimage

The idea of pilgrimage – a spiritual journey to a sacred place – is buried deep within our understanding of spirituality and religious practice.

The practice of making a special journey to a place where significant spiritual events have occurred, along a route made holy in itself by the numberless thousands who have made the journey before, and, on arrival at the site, of connecting somehow with the events that took place there, has had a huge influence not only on the spiritual history of the British Isles but also on the physical infrastructure. Routes were laid down by the feet of the faithful travellers, glorious cathedrals made possible by the donations of those who visited places where relics lay in state, and a network of abbeys built to support the needs of those travellers.

For many hundreds of years, even during times when injunctions were made by religious leaders against the practice, men and women hoping for healing, revelation or spiritual insight have travelled to places where, it is felt, the gap between heaven and earth is smaller, where the actions of saints may break into the lives of ordinary people, transforming them.

‘For hundreds of years, men and women hoping for healing, revelation or spiritual insight have travelled to places where the gap between heaven and earth is smaller.’

It was not only the major sites that became ever more popular as a way of expressing devotion to the saints. Gradually a body of history developed on the lives and actions of local saints, missionaries to the shores of Britain who sought to carry the news of the gospel to this hostile land. The places where miracles and revelations occurred – healings, conversions, miraculous events – became, in their turn, sacred, although on a more domestic scale. Each pilgrimage, however short, afforded an insight into the spirituality of the journey.

Iona, Lindisfarne, Walsingham, Canterbury… As pilgrimage became part of English religious practice, the country was crossed and recrossed with pilgrimage routes, encouraging trade and a growing range of businesses dedicated to the needs of pilgrims.

But concerns arose in some quarters that such journeys were not always undertaken in the correct spirit. Those seeds of decline were fertilised by the growing danger of travel through not only the Middle East but Europe itself, and they came to fruition with the Reformation in the 16th century, when both the church and the state worked to suppress the phenomenon of pilgrimage.

‘Iona, Lindisfarne, Walsingham, Canterbury – pilgrimage became part of English religious practice.’

It was better to spend the money on the poor than on travel, it was argued, especially when opportunities for misbehaviour were so plentiful. The interior journey was thought to be the best pilgrimage. Also, the pilgrim destinations, where the body parts of dead saints were knelt by and prayed at, were beginning to be seen as idolatrous. Gradually, during the 16th century, most of the shrines throughout Protestant Britain and Europe were destroyed, with a corresponding growth of emphasis on the internal or spiritual pilgrimage, the inner journey of faith.

In time, the rise of the Romantic and Neo-Gothic movements brought pilgrimage once again into the realms of acceptable practice. The 19th century saw a resurgence of interest in the Holy Land and Rome. The appearance of the Virgin Mary to a 14-year-old girl at Lourdes in 1858 gave rise to a new site, dedicated to healing, with other sites, including Fatima, Taizé and Medugorje, gaining credence in the 20th century.

The numbers of people undertaking pilgrimages both within the UK and further afield are now growing year by year. An awareness of the possibilities of pilgrimage is becoming a significant part of Christian spirituality once more, bringing with it opportunities even for those for whom a journey to distant lands is not a possibility. A wealth of information is available, including the following sites and online articles:

- The Centre for Christian Pilgrimage

- British Pilgrimage Trust

- Methodist Church pilgrimage resources

- The Confraternity of St James

- ‘Northern Saints Trail launched in Durham’

- ‘Cathedrals cycle routes announced’

- ‘Pilgrim routes in Scotland’

- ‘Popularity of pilgrimage booming’ in The Scottish Catholic

And check out your local diocesan and cathedral websites.

Sally Welch is diocesan canon of Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford, and co-director of the Centre for Christian Pilgrimage. Previously she was a parish priest of 20 years’ standing, having ministered in both urban and rural settings in the diocese of Oxford. Sally is a committed pilgrim and has walked many pilgrim routes in the UK and Europe, with plans for many more. She is the author of several books on pilgrimage and has lectured and led workshops on the nature and spirituality of pilgrimage throughout the UK.

In Pilgrim Journeys Sally Welch explores the less-travelled pilgrim routes of the UK and beyond, through the eyes of the pilgrims who walk them. Each chapter explores a different aspect of pilgrimage, offering reflections and indicating some of the spiritual lessons to be learned that may be practised at home.

Sally has been editor of New Daylight Bible reading notes for many years but the current issue is her last before Gordon Giles takes over the role. Readers are enjoying her series of reflections on Rivers, which runs until Tuesday 31 August.

Families whose children aren’t quite at the pilgrimage stage might enjoy this short Parenting for Faith video on how to survive the journey.

The journey

There’s a great outline for a Pilgrim’s Progress-based activity and reflection session on the BRF Resource Hub. Suitable for Sunday school, holiday club and the classroom.