Three BRF Ministries authors help you think through the questions and reflect prayerfully on the gospel values that might guide your decision-making in the election on 4 July. This week, Jonathan Arnold on social justice, in an extract from his new book The Everyday God.

16 June 2024

Social justice, not just social policy

In his Nazareth manifesto in Luke 4, Jesus proclaims that his life and ministry have, in the words of Bishop Sheppard’s 1983 book, a bias to the poor: to bring good news to the poor, let the oppressed go free. Echoing the words of Mary’s Magnificat, Luke’s Jesus proclaims that in the new kingdom of God, ‘He has brought down the powerful from their thrones, and lifted up the lowly; he has filled the hungry with good things and sent the rich away empty’ (Luke 1:52–53).

Such texts remind us that the good use of power is about empowerment, about enabling others to have agency and dignity, grounded in the truth that we are made in the image of God, loved by God, and that each one of us is unique and beautiful to the one who made us. As God proclaimed: ‘Before I formed you in the womb I knew you’ (Jeremiah 1:5).

This dignity is also based in solidarity. We belong to each other. Or in the Zulu philosophy of ubuntu: ‘I am because we are.’ This common humanity leads to a common good in terms of material things. The fruits of the earth are everyone’s. As St Ambrose wrote, when you give to the poor, ‘you are not making a gift of your possessions to the poor person. You are handing over to them what is theirs.’

When you give to the poor, you are are handing over to them what is theirs.

An individual and communal responsibility

Christ’s manifesto in Luke’s gospel and the command to do works of mercy, found in Matthew’s gospel, show us God’s bias towards the poor and vulnerable, to whom we respond from a common and God-given human dignity, solidarity and goodness. Therefore, we cannot simply rely on political or social policy to do this work for us, important though that may be. We all have an individual and communal responsibility, following in the footsteps of Christ, to care for the least privileged in our communities.

In John Rawls’ 1971 work A Theory of Justice, he argues that benevolence or sentiment are inadequate to bring about social justice. He declares that social justice must be institutional and part of the basic structures of society. It is fundamentally a secular argument that political social justice is the parent to individual acts of social justice. This is based upon two principles, espoused by the German Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant: first, equality of basic liberties and opportunities for self-advancement are more important than social welfare; and second, the distribution of goods and opportunities work to the advancement of all.

However, as Philip Booth has counter-argued, there are problems with placing all our hopes for society in political or capitalist ideologies.

We all have an individual and communal responsibility, following in the footsteps of Christ, to care for the least privileged in our communities.

Catholic social teaching

Citing the Catholic document Gaudium et Spes (‘Joy and Hope’), one of the four constitutions arising from the Second Vatican Council of 1965, Booth quotes: ‘The common good embraces the sum of those conditions of the social life whereby men, families and associations more adequately and readily may attain their own perfection’ – in other words, bringing the world closer to the perfection of the kingdom of God on earth. Fulfilment and perfection are not subjective categories, he argues, because Christian social justice requires that fulfilment and perfection are found in relationship to God and our relationship with our neighbours.

So, while we need social conditions that can bring about the common ‘good’ for all, Christian social justice is not totally, or even primarily, about policy, because it is more than mere utilitarianism – that is, the greatest good for the greatest number – nor is it about general welfare. It is about human beings taking personal responsibility for caring for each other.

As Booth reminds us, history tells us that millions have died because of nations putting all their trust in centralised systems of government that become totalitarian. Systems that start off with high ideals and great intentions can end up being oppressive and corrupt, as we have seen time and time again in history. And religious institutions can easily have a similar tendency, if given similar autocratic and absolute power. Once an individual delegates responsibility totally to the state or an organised religion, it can lead to corruption.

Secondly, handing over responsibility or power to a system denies the fact that doing ‘good’ is always an individual choice, a personal response to God, and cannot be delegated. It is called free will.

And third, asking governments to create systems that provide universal social justice is impossible. There are always unintended consequences of policy, which compromise the success of any system. Social justice is not just a distribution of wealth but actions that contribute towards the common good.

Social justice is not just a distribution of wealth but actions that contribute towards the common good.

Jesus and justice

The type of social justice this book deals with, the justice of Luke 4 and Matthew 25, is nicely summarised in a Salvation Army booklet called Jesus and Justice: Living right and righting wrongs, which states:

Jesus’ mission is captured in a single vision with two dimensions. His hope for a restored humanity envisions well-being for people who are spiritually poor and people who are socially poor. And in their midst, righteousness and justice mark the events of his days and nights. Jesus lives right and makes life right with others. In Jesus’ code, to love is to be just. To be just is to love. And when we claim to follow Jesus we are disciples of justice. Jesus’ mission on earth in his time is our mission on earth in our time.

Thus, as John Wesley wrote, we meet Christ when we serve with and get to know people who are suffering. When we go outside our comfort zone, Christ gives us grace. In this uncomfortable place Jesus is our example:

Jesus’ life is a demonstration of how to live and love. Jesus incarnated intentional love. He demonstrated willful, purposeful and creative love; love for God, self, neighbour, truth, righteousness and justice. Jesus envisioned what didn’t yet exist. He championed freedom from oppression – discrimination, exclusion, inequality, poverty, sin and injustice.

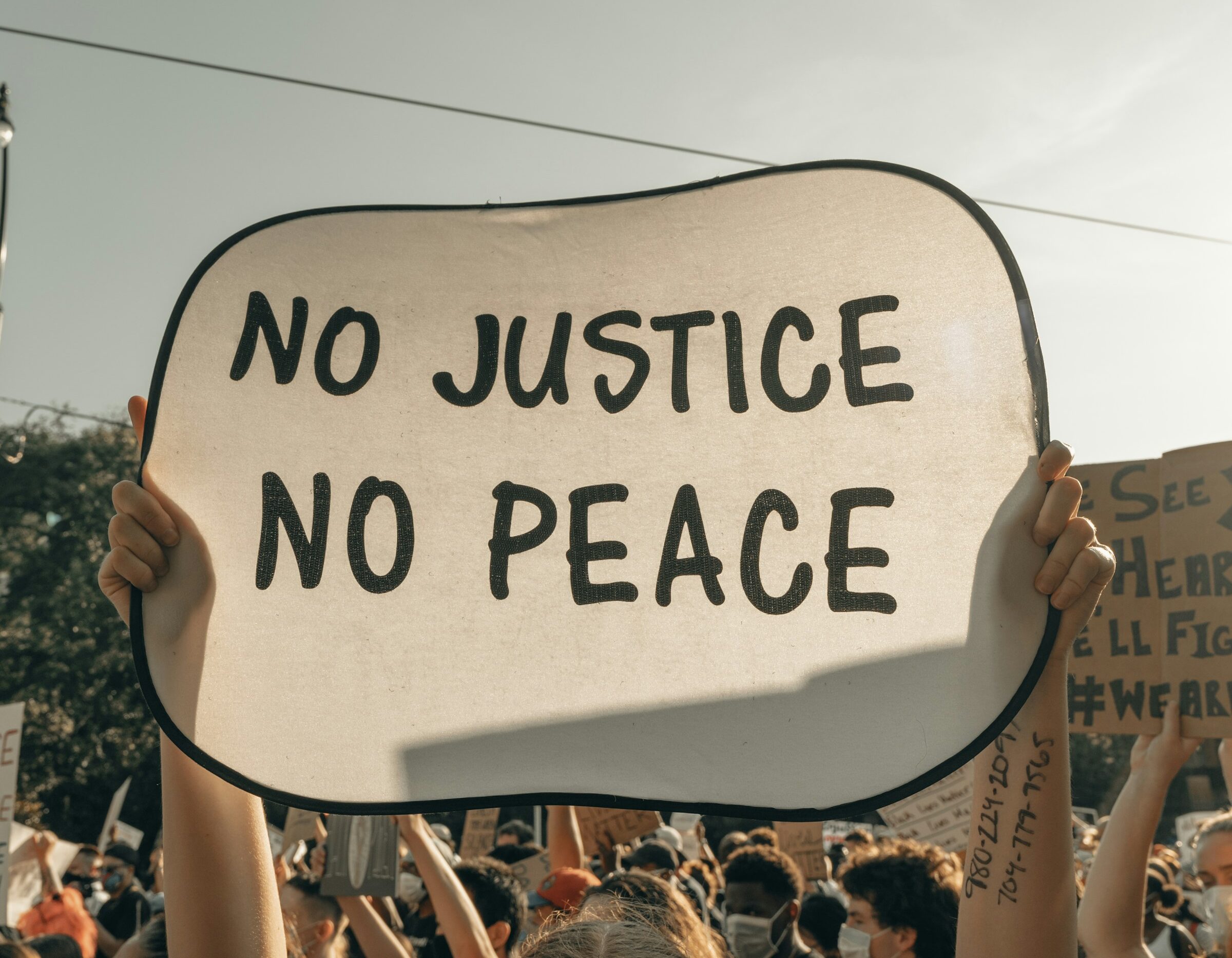

Thus, Jesus had a vision that the oppressed would be freed and wrongs would be righted where political and legal systems had failed. In this world, in which we still live with visions of hope for a world where dignity and fairness reign, we must imagine it and enact that vision, for we live in the tension of the ‘now and the not yet’ of God’s kingdom.

We meet Christ when we serve with and get to know people who are suffering.

Justice for the poor

Do you remember the Make Poverty History campaign of 2005? There were global campaigns for trade justice, the wiping clean of certain debts and for better aid. It was a time when people were imagining a better future, and hopeful that it could come about given the right pressure on world leaders. Alas, poverty has not become history and the gap between rich and poor has if anything become wider. One of the main reasons that poverty prevails is the apathy of the rich.

In the Acts of the Apostles we do not find the young Christian community apathetic to poverty. Quite the reverse. But what might be surprising is that their response to poverty is, as Craig Gardiner asserts in his book Melodies of a New Monasticism, not only one of financial recompense, but also one of justice: ‘The embryonic Christian community soon responded to this challenge [of poverty] with melodies of “compassion and action” beginning a radical and sacrificial provision for the poor among them.’

Correcting the wrongs of a society that apathetically allows poverty to persist can be, as Gardiner says, radical and sacrificial. This is why, alongside the compassion of mercy, we need a fire in our bellies that demands justice. As Martin Charlesworth and Natalie Williams write in The Myth of the Undeserving Poor:

God is a God of justice… This means that his children are to love justice and hate injustice too… In relation to the poor, it seeks for them not to be disadvantaged due to lack of wealth or status, but to be elevated, valued, and given a voice.

And so, in addition to the ‘constructive justice’ of our political and legal systems, we need ‘corrective justice’. We have the strength to persist in this practice of corrective, or social, justice, because we are joining in with a work already begun, the music of Christ’s melody of mercy.