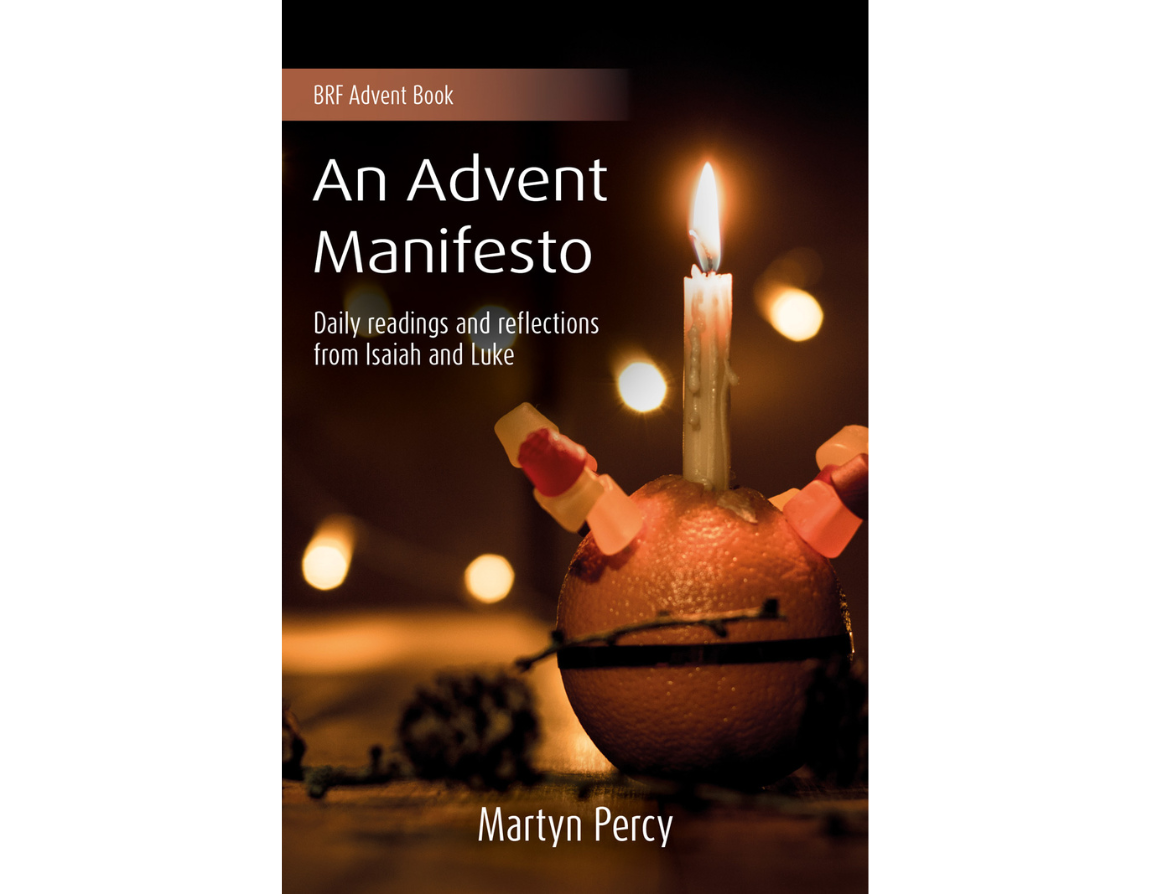

The last in a series of articles by Martyn Percy, linked to themes in his An Advent Manifesto, our 2023 Advent book.

10 December 2023

A mystical–political Advent theology

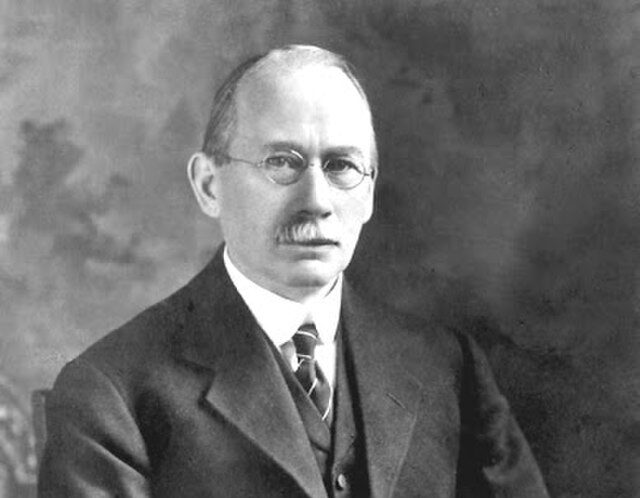

In his extraordinary book Jesus and the Disinherited, first published in 1949, Howard Thurman suggested that the church needed to recover a reading of the gospel as a manual of resistance for the poor and disenfranchised. The alienation, oppression, marginalisation and violence experienced by the African American are central to the religion of Jesus. Thurman’s goal was to offer an emancipatory way of reading, being and moving in Christianity, leading to a fundamentally unchained life available to people everywhere.

A casual reader might see this as an early version of liberation theology, but I think it’s much more than that. Thurman argues that within Jesus’ life of suffering, pain and overwhelming love is a means of preventing humanity’s descent into moral nihilism. Jesus, though scorned and forced to live outside society, nonetheless advocated a love of self and for others that defeated fear and hatred: the very forces that decay our souls and the world around us.

Thurman was attentive to the fear that dominates people with no rights, and to the fear that dominates those who have the rights but refuse to let go of their power. He was also attentive to the way forces of hate shaped and dominated religious and social constructions of reality in the time of Jesus and in our time now. Above all, he knew the importance of establishing a love ethic at the centre of justice and truth in order that there might be equality and empowerment.

Thurman writes:

‘Too often Christianity seems impotent to deal radically and effectively with issues of discrimination and injustice on the basis of race, national origin, gender, or sexuality. This is not a weakness in the religion itself: it absolutely is a weakness in the people who wrong religions, and deny the disempowerment that is visited upon others. The conventional term “Christianity” is too often muffled, confused and vague. It colludes with powers in society that are invested in security and respectability. The Jesus who emerges in first-century Palestine is someone who raises the spectre of a new Kingdom, and the possibility of people being born again into a living hope which is revolutionary and will turn the world upside down.’

‘The Jesus who emerges in first-century Palestine is someone who raises the spectre of a new Kingdom, and the possibility of people being born again into a living hope which is revolutionary and will turn the world upside down.’ —Howard Thurman

Left: Howard Thurman portrait, detail of stained glass window, Howard University chapel (photo by Fourandsixty, CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED, cropped)

A lifespan of dramatic change

Thurman lived from 1899 to 1981, a lifespan covering a period of dramatic change in the United States. The experience of slavery was still fresh in the memory and the behaviours of many African Americans. Discrimination and segregation had been legal for the vast majority of his life. The Great Depression, two World Wars, the Korean War, the Vietnam War and the Cold War had mobilised and spent the energies of a nation and many of these collective traumas affected black people disproportionately.

Throughout Thurman’s life, black people were treated as marginal, subordinate and expendable. He came to see that it was the culture that needed to be addressed if the love and light of God was to emerge in Advent radiance. For Thurman, social questions were also religious questions. Repeatedly he asks: ‘How can I believe that life has meaning if I’m not allowed to believe my own life has meaning?’

Studies in mysticism

Part of the early formation of Thurman’s theology lay in his time at Haverford College with the Quaker mystic and scholar Rufus Jones. Jones guided Thurman’s extensive study in mysticism, and Thurman would later describe this as a watershed experience, the effects of which flow through his subsequent thought and endeavour, and to which he committed the rest of his working life.

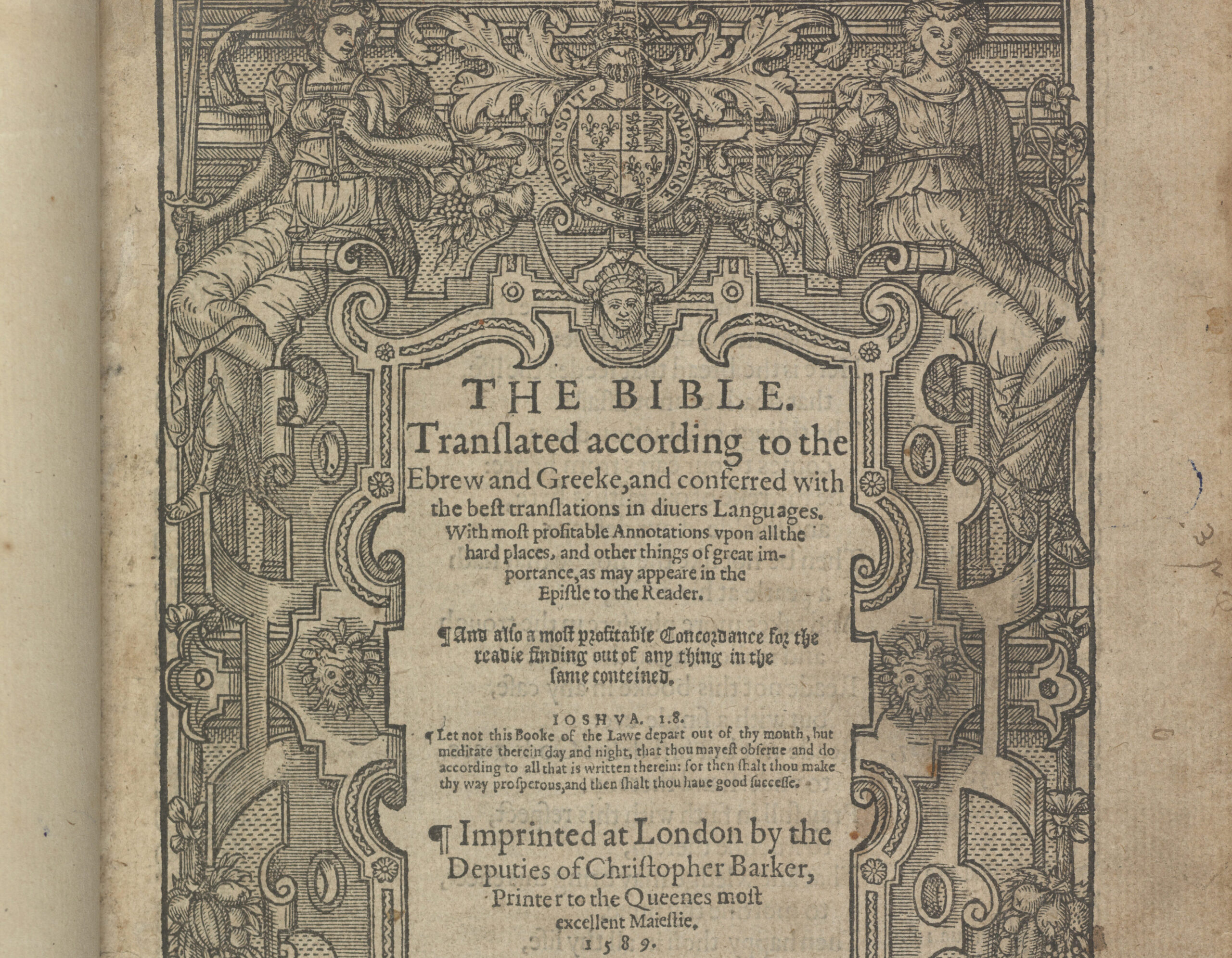

In An Advent Manifesto, I’ve made a few observations about the Bible translations people use. The Geneva Bible of 1560 was a translation by Protestants who had fled to Geneva during the reign of Mary I (1553–58). The translation was the first mass-printing available in the English language, and included cross-references and notes. The Geneva Bible contained over 40 references to ‘tyrant’ and ‘tyranny’ in translation.

In contrast, the King James’ Bible, decreed to be regarded as the Authorised Version (note the title!), forbade the use of these words. But it was the Geneva Bible that Oliver Cromwell’s soldiers marched with, that Mayflower pilgrims took to their promised land. The longing for freedom from monarchy and tyranny underpinned their understanding of God’s word.

It was the Geneva Bible that Oliver Cromwell’s soldiers marched with, that Mayflower pilgrims took to their promised land. The longing for freedom from monarchy and tyranny underpinned their understanding of God’s word.

Biblical freedom

Biblical freedom is not just for us. It is to be extended to everyone. Many of the authors of the Old Testament promoted a form of ‘positive liberty’ that was based on a just social order. Leviticus, for example, demands that those who lose their livelihoods are supported by their neighbours. The lives, lands and livestock of the vulnerable are protected. The Old Testament holiness code is one that promotes interdependence. The holiness code also limits the power of the monarch. The king must be one of your own kin (Deuteronomy 17:14–20) and not above the citizens. Crucially, the only role the monarch has is to study, practice, dispense and obey the law.

The laws themselves are understood to be directly mediated revelations from God. They represent the covenant between God and humanity and turn the legal code into an apotheosis of sorts. The monarch must be subject to that law too. The covenant is also a dynamic reminder of Israel’s fate when it was denied rights and legal protection: ‘Remember that you were a slave in Egypt… God redeemed you from there. I, God, therefore command you to observe and protect the rights of the orphan, widow, alien and vulnerable’ (see Deuteronomy 24:18–22).

For Thurman, the search for humanity and justice was rooted in the great arc of the commandments God sets down to the children of Israel, and indeed to all humanity. Again, he writes:

‘There is a spirit in man and in the world working always against the things that destroy and lay waste. Always he must know that the contradictions of life are not final or ultimate: you must distinguish between failure and a many-sided awareness so that you will not mistake conformity for harmony, uniformity for synthesis. He will know that for all men to be alike is the death of life in man, and yet perceive the harmony that transcends all diversities, and in which diversity finds its richness and significance.’

Everything Thurman wrote and taught flowed from the life, work and person of Jesus of Nazareth and from his incontrovertible encounter with the mysticism of the Quaker Rufus Jones.

The search for common ground

Thurman understood that no one could be a moral actor alone. Like a burning coal, on its own it would quickly go cold. The search for common ground was therefore something that shared spark, heat, warmth. The enemies of humanity and sociality were therefore for discrimination and marginalisation. Anything that pushed people out from the centre and isolated and demeaned them was not just evil and wrong visited on those people, it was also something that denied the centre of its own inner true soul and authenticity.

In the tradition of the Hebrew prophets, Thurman called on both America and Christianity to recall the source of their identity and to serve as a lantern of hope to those who sought to serve, to speak truth to power and transform the nation and the world. Everything Thurman wrote and taught flowed from the life, work and person of Jesus of Nazareth and from his incontrovertible encounter with the mysticism of the Quaker Rufus Jones.

It’s because he embodied this truth, and trusted other people to embody theirs, that his vision of human community was generous to generations, and therefore the ground of spiritual territory that was rooted in the life and work of Jesus.

Thurman was a practitioner of what we might call ‘ethical mysticism’. He subverted perceptions of the real and the unreal. The ‘real’, as it were, funded his courage to challenge the ‘unreal’ in all its guises: unjustness, unkindness, irreconciliation, lack of freedom.

He understood empirically that we live amid mysteries that will forever evade our full understanding: not least the mysteries of God, the human self, community and our callings to serve in a suffering world. But ethical mysticism always demanded community, equality, enlightenment and humility. May ethical mysticism be our manifesto this Advent.