In the first of our summer series drawn from the new issues of our Bible reading notes, Isabelle Hamley takes us on ‘A journey in discipleship through Luke 9–16’ in Guidelines, September-December 2024.

4 August 2024

‘Lord, teach us’

The phrase ‘Lord, teach us’ encapsulates the middle section (chapters 9—16) of the gospel of Luke. Jesus teaches through word and example, through story and short, pithy sayings, through healings and deliverance, in inviting the disciples to join him and sending them out themselves. As he does so, a picture of discipleship and of the shape of the community that Jesus is gathering gradually emerges. It is a community shaped by the values of the kingdom of God – radical alternative ways of thinking, behaving and relating that nurture the flourishing of all at the expense of none.

Perhaps the most salient aspect of Jesus’ teaching in these eight chapters is the sheer volume of sayings and stories about wealth and its associated status and power. Wealth is not condemned as intrinsically wrong, though it can be wrongly acquired. However, wealth that is not used for the welfare of all, wealth that does not lead to the blessing of the entire community, can be a burden and a curse to the one who holds it. Similarly, those with status and power are called, again and again, to use it for the benefit of all, whether this is exercised in an economic, political or religious sphere. Jesus is clearly concerned, not just with individuals, but with communities, their lives together and the way in which our daily choices shape the health and flourishing of those around us.

Perhaps the most salient aspect of Jesus’ teaching in Luke 9—16 is the sheer volume of sayings and stories about wealth and its associated status and power.

Expanding the imagination

In Luke 10:1–24 Luke tells a story remarkably similar to the one that opened chapter 9: the sending out of the 72, with instructions similar to those given to the twelve, but expanded. The progress of the narrative through Luke and Acts shows how ever-widening circles of disciples are brought into the proclamation of the kingdom of God. The story is darker here than in chapter 9. Following the disciples’ struggles to understand the message, and rejection in Samaria, the themes of rejection and judgement take on more prominence. The challenge of the gospel and the cost of discipleship become embodied in the reality of conflict.

In today’s world, churches in decline often try to make the gospel more attractive or see rejection as a sign of failure on their part. This passage in Luke, however, reminds us that rejection was the experience of Jesus and of early disciples, because the gospel is good news, but it is not easy. The demands of the gospel are obvious in the instructions to the 72. They are to go out with no purse, no bag and no sandals (v. 4). In other words, no containers for worldly goods and no sign of wealth. It is an instruction to operate outside of economic norms of service and payment and outside of the norms of sensible, prudent provision ahead of journeys. It is a call back to the desert in Exodus, when Israel was led by God into a place of utter scarcity and asked to trust in God’s provision.

This kind of instruction demands a radical shift of the imagination, the ability to imagine that different ways to live and to relate are possible. It demands trust and the belief that human life and survival are essentially relational, rather than based on individual planning and provision-making. Obliquely, it is a challenge to the economic thinking of the Roman empire and every other system that has sought the accumulation of riches as a marker of success.

Jesus proclaims that the kingdom of God is ruled by different principles – abundance, faith, trust and generosity – which are neither naïve nor a pipe dream. But this is hard teaching, and the disciples are not always welcome.

And yet, whether they are met with peace and welcome or with rejection, the message and the invitation are the same: the kingdom of God is near.

Jesus’ most salient challenge is, perhaps, the challenge to let our imaginations be transformed by a picture of the kingdom that is so alien, so different from our ways of living and structuring our communities, that it completely disrupts our expectations about relationships, money and possessions and the degree to which we trust God for all we need.

This kind of instruction demands trust and the belief that human life and survival are essentially relational, rather than based on individual planning and provision-making.

Mending relationships

Jesus said more about money than he did about prayer or sex – even though the fact is not always obvious in our lives or our churches. In Luke 12:13–21 he again offers some hard teaching, tempered by a wider assurance of God’s loving care.

A man comes and asks for his help. The man’s cry is a cry for justice. In all likelihood, his father had died without a will. Under these circumstances, the younger brother would be left landless unless the older brother agreed the property could be divided up. Why doesn’t Jesus help? Jesus’ answer – ‘Who set me to be a judge over you?’ – shows that Jesus refuses to be drawn into a family quarrel and risk undermining the relationship further. His authority would be unlikely to be recognised by the older brother and any pronouncement would deepen the rift. Jesus does not know the whole story or all involved. Justice cannot be completely one-sided, nor can it properly happen independently of the mending of relationships.

The cost of indifference

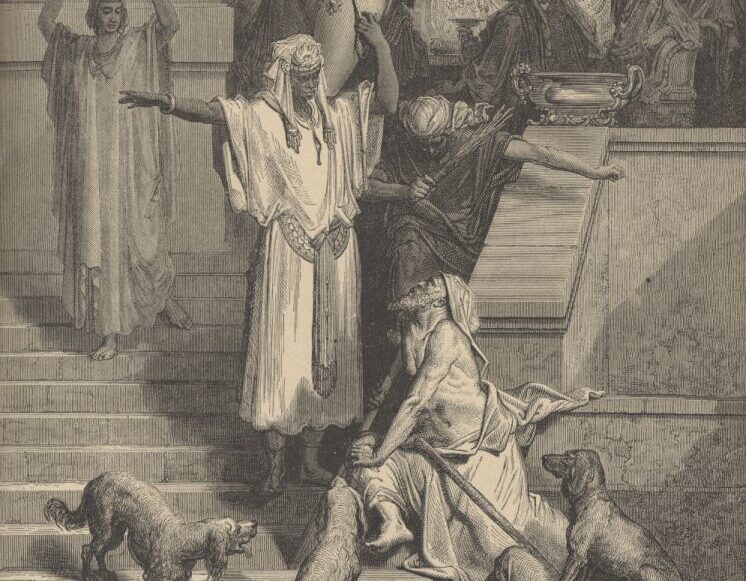

Luke 16 closes with yet another parable that addresses social injustice, the power of wealth and the call for disciples to heed the teaching of the law on how to live well as communities. The message is straightforward, but small details give depth and texture to the story.

Lazarus is the only character ever named in Jesus’ parables; his name means ‘God is my help’, which seems ironic in light of his circumstances. Yet in death, he finds comfort, and the rich man longs to become the one who is helped but finds that he is not. When Lazarus lay at the rich man’s gate, waiting for leftovers from the rich man’s banquet, food was given to the dogs. Dogs were not beloved pets but symbols of wildness and uncleanness, yet they were treated better than Lazarus. Dogs lick their own wounds and the people they love. Here they lick Lazarus’ wounds, in a gesture that shows they care more about Lazarus than the rich man does

The story exemplifies how deeply wealth and status can affect our ability to see the world for what it is.

When the scene shifts to a heavenly realm, it would be easy to think it is a simple reversal of fortunes; but the text is not so crude as to suggest that if you have a good life you go to hell, and a bad life, to heaven. Instead, the story shows that even when faced with torment and evidence of his hard-heartedness, the rich man still does not get it. He demands that Lazarus be sent to help him, when he had never helped Lazarus. He still treats Lazarus as inferior and does not address him directly. Instead of reflecting on why he finds himself where he is, he uses being a descendant of Abraham to try to get help. His mind is totally shaped by fixed ideas of class, status and privilege. Even when confronted by Abraham, he still cannot see what the problem really is, does not apologise to Lazarus or acknowledge his own hardness of heart.

The story exemplifies how deeply wealth and status can affect our ability to see the world for what it is and to respond in ways shaped by the gospel. Not all rich men are baddies in Jesus’ parables – there are masters who become servants, others who act generously and fathers who forgive. The key with all of them is that they turn privilege into blessings for those around them.