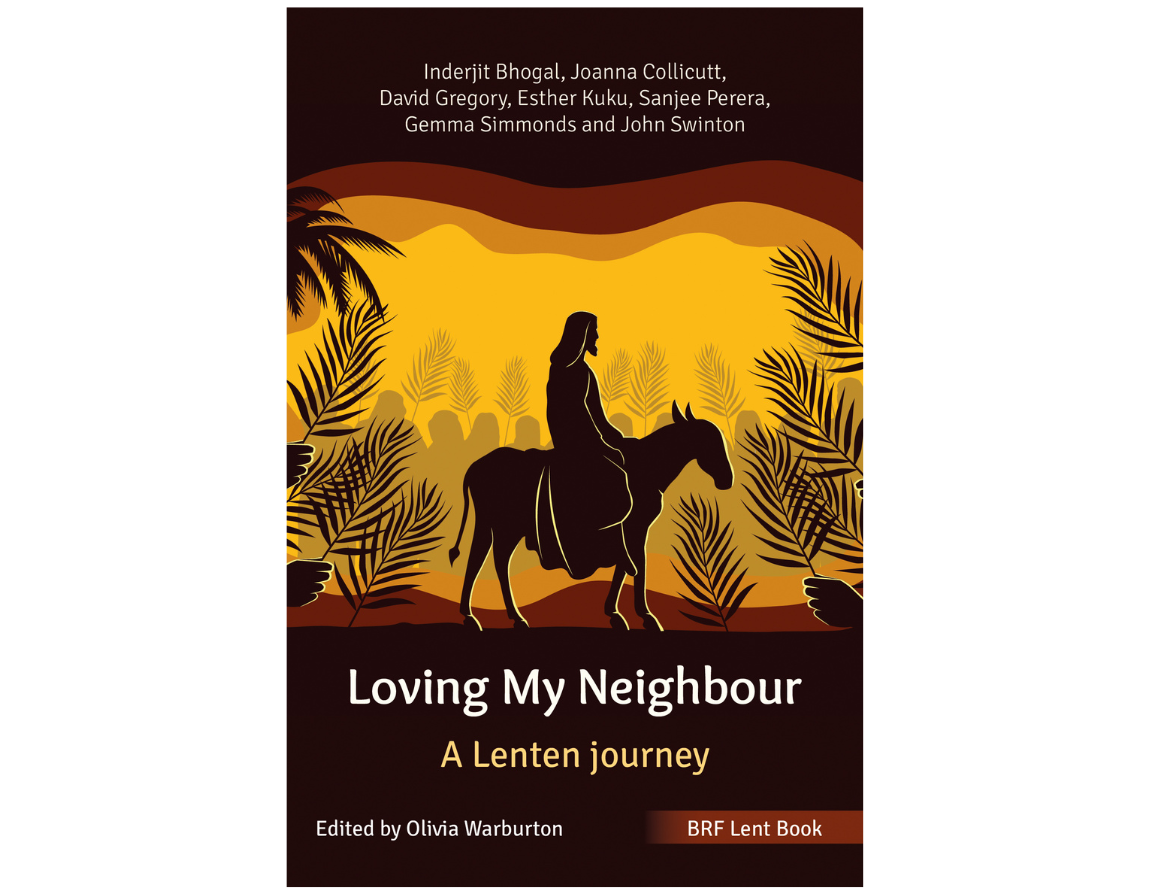

Our 2024 Lent book Loving My Neighbour focuses right to the heart of discipleship and what living out our faith really looks like. Bringing together well-respected voices from across the church, it offers a broad and diverse range of perspectives on the biblical imperative to love our neighbour, and provides thoughtful encouragement as we seek to live this out in today’s context, through Lent and beyond. In this week’s excerpt, John Swinton looks at ‘Loving those who are vulnerable’.

18 February 2024

An upside-down kingdom

Then the righteous will answer him, ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you something to drink? When did we see you a stranger and invite you in, or needing clothes and clothe you? When did we see you ill or in prison and go to visit you?’ The King will reply, ‘Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.’

Matthew 25:37–40 (NIV)

One of the most startling things about the gospel is the way in which it reverses cultural norms. In situations where it seems ‘obvious’ that the strong and the powerful are the role models for a good society, scripture reveals that it is in fact in our weakness and vulnerability that we discover the important things in life (2 Corinthians 12:9–11). It is as we slow down and take time to look at and care for one another that we discover what it means to worship a God who is love (1 John 4:8). As we are invited into the upside-down kingdom, we meet a Saviour who gives his life that we may experience and find rest in God’s love (John 3:16).

That Saviour offers us both peace and dissonance. The peace comes as we discover that amid the storms of this world there is a peaceful centre and an overwhelming movement towards a final destination where there will be no more suffering, no more tears and no more goodbyes (Revelation 21:1–4). The dissonance emerges when we realise that we are called to be harbingers of this new upside-down kingdom. It is us (all of us together) who are called to embody the life of Jesus and to allow the Holy Spirit to transform our vision (Romans 12:2) and our bodies (1 Corinthians 6:19–20), in such a way that we crave justice and love even to the extent that we may lay down our lives for our friends (John 15:13).

When we reflect on the upside-down kingdom, we come to realise that the broken, the marginalised, the oppressed, the lost are more important than anything else. We also discover that ‘they’ are in fact ‘us’ (Matthew 25:40).

When we reflect on the upside-down kingdom, we come to realise that the broken, the marginalised, the oppressed, the lost are more important than anything else.

The reversal of power

There is a beautiful photo of Cardinal Bergoglio (who later became Pope Francis) kneeling at the feet of a child in a wheelchair. It is clear from the picture that the child has some kind of terminal illness. He is thin, emaciated, vulnerable and wears a surgical mask for fear of infection.

It is a powerful vision of humility and the reversal of power. One of the most powerful religious leaders in the world prostrates himself before one of the most vulnerable people in the world. There is a crowd around the cardinal and the boy, watching, pushing in. But even in the midst of the pressing crowd, the cardinal takes time to be with the boy. In humility he bows down and kisses the boy’s feet.

One is immediately struck as to the way in which the cardinal positions himself before the boy. He kneels and looks downwards. He adopts the same posture before the boy as he would take if he was worshipping Jesus, the one who claimed he was with, for and within ‘the least of these’ (Matthew 25:40).

Secondly, as he adopts this posture, the cardinal inevitably sees things very differently from the way he might see things if he was standing up and towering over the boy. Looking at vulnerability from a position of power is very different from looking at it from a position of weakness and humility. The posture of the cardinal is one of a guest. Like Jesus, he does not try to host the child, try to draw the boy into his world in order to care for him on the cardinal’s terms. Rather, he accepts the boy’s hospitality, and in accepting that hospitality he receives the gift of knowledge – knowledge of what it’s like to view life from ‘down there’. He sees things in a different way, feels things differently. He opens himself to the way that the boy sees the world and becomes open to the gifts of sadness and joy that such a revelation brings with it.

Looking at vulnerability from a position of power is very different from looking at it from a position of weakness and humility.

Divine hospitality

One of the fascinating things about Jesus’ hospitality is that it was marked by a constant movement from guest to host. Sometimes he was a guest in people’s houses, at other times he was a host. This is made even more poignant by the fact that Jesus at this stage in his ministry did not have a home. It is this profound movement from guest to host that marks divine hospitality.

What might it be like if we allowed this vision of divine hospitality to change, shape and form us? What would it look like if we became hospitable people who truly welcomed those whom the world considers to be strangers? What would it be like to be a guest in the life of an asylum seeker rather than assuming that we are hosts? What would it look like to be a guest in the life of people who, in the midst of the wealth of our country, struggle to find enough food to feed their children? What if we were truly to live like Jesus calls us to live?

It was Thomas Merton who pointed out that as God’s creatures, ‘Our job is to love others without stopping to inquire whether or not they are worthy.’* That love reveals itself in our hospitality towards those whom we know, and those who, for now, are strangers to us. In the hospitality and gestures of love revealed by the friends of Jesus, love is made available to the world.

* In a letter to Dorothy Day. See Jim Forest, ‘The spiritual roots of protest’, in Stephen Hand (ed.), Catholic Voices in a World on Fire (Lulu Enterprises, 2005), p. 180.