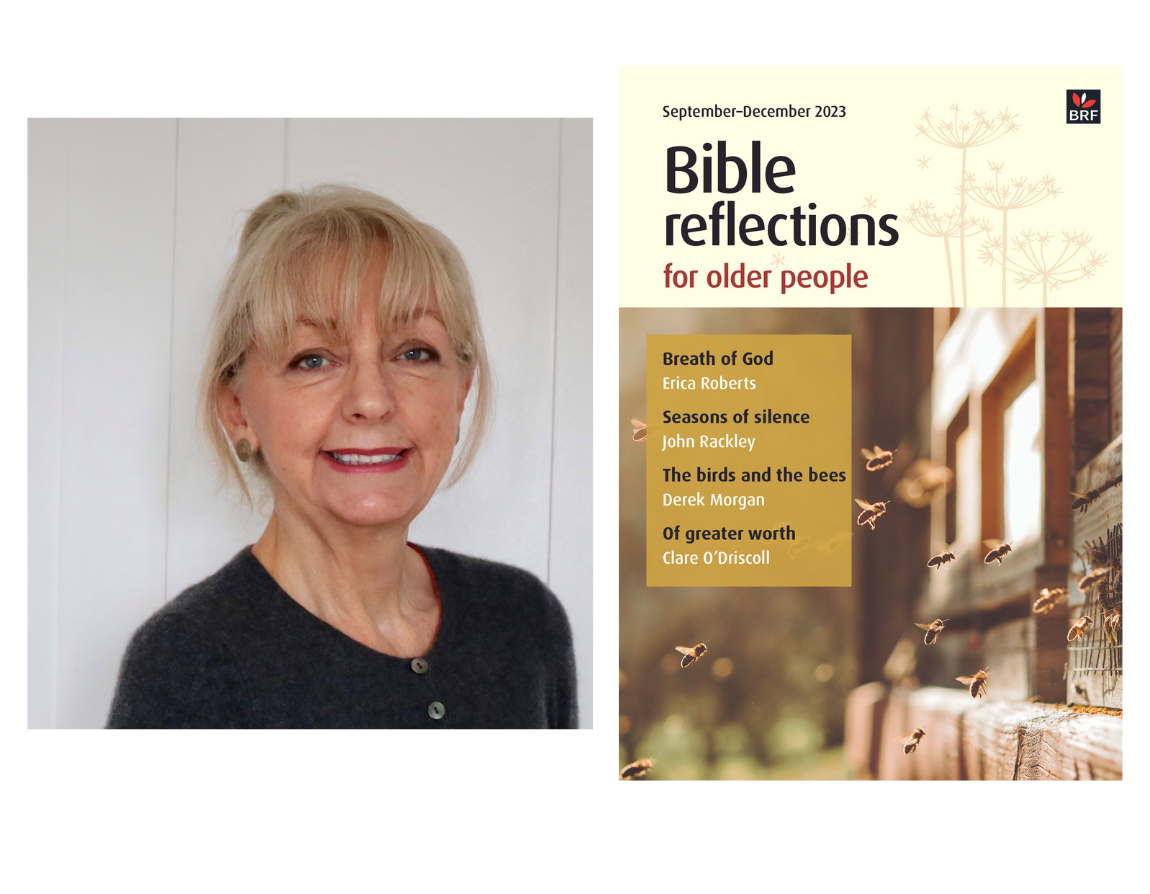

To mark Remembrance Sunday, Eley McAinsh, editor of Bible Reflections for Older People, reflects on memory and remembrance.

12 November 2023

Even once deep in the fog of dementia, my dear dad, Ken, remained a proud engineer. He would occasionally amaze us by asking detailed technical questions about my brother’s latest racing car design, or by working out complex calculations for the storage of solar energy with a slide rule. Yet he had no short-term memory, his mobile phone had long defeated him and he called my brother by the name of his childhood friend, Jimmy.

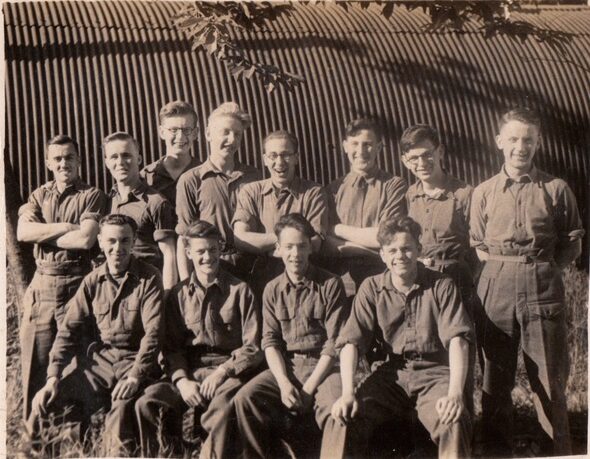

Dad’s oldest memories were the most vivid. One of my sisters made a beautiful hardback album of grainy black-and-white photos of his time as a young army officer in Singapore, just after what he called ‘the shooting war’ finished. Always profoundly grateful to have missed the fate of so many of his only slightly older school friends, his two years in the army – the things he saw, the experiences he had, the responsibilities he shouldered – were formative, and became an enduring part of his sense of identity. We all spent hours with him in his airy care home room, pouring over those pictures time and again, listening to the stories, watching his face light up as he remembered and reconnected with such an important part of himself.

We all spent hours with him, pouring over those pictures time and again, listening to the stories, watching his face light up as he remembered and reconnected with such an important part of himself.

Left: 2nd Lieutenant Kenneth McAinsh with his driver, Singapore 1947.

The Great Escaper

When news broke in June 2014 that 89-year-old navy veteran Bernard Jordan had gone AWOL from his Sussex care home to attend the 70th anniversary commemorations of the D-Day landings in Normandy, Dad stirred. Alert and engaged, he cheered Bernard on from his armchair and, I’m sure, fleetingly imagined his own escape plan.

And so it was that I came to spend a recent afternoon quietly crying my way through The Great Escaper, the touching new film with Michael Caine and Glenda Jackson that tells Bernard’s story. Bernard had been very much involved in ‘the shooting war’, and was deeply scarred by his experiences. Haunted by flashbacks, tormented with guilt, his tortured memories are somehow healed, finally laid to rest, amid the pristine rows of white headstones in the War Grave Commission cemetery at Bayeux.

In this season of Remembrance – embracing All Souls and All Saints Days as well as Armistice Day and Remembrance Sunday – questions of memory and remembrance become public and communal as well as private and personal. To mark the season, Messy Church lead Aike Kennett-Brown and Anna Chaplaincy lead Debbie Thrower explored some of these questions in a warm, wide-ranging conversation on Facebook.

In this season of Remembrance, questions of memory and remembrance become public and communal as well as private and personal.

Right: Ken with his fellow junior officers at the Bukit Timah Road camp.

A listening presence

One part of the exchange struck me particularly. Debbie spoke about the ‘identity crisis’ that many older people experience when those aspects of life which gave them their sense of self, purpose and place in the world have gone. ‘That’s why,’ she explained, ‘so much of an Anna Chaplain’s ministry is to be a listening presence.’ Trained as ‘expert listeners’, they encourage the older people they work among to share their stories, and in the sharing they are heard and affirmed. As Debbie said: ‘Having someone who’s a really good, sympathetic listener can be such a bonus for people.’

Through all Dad’s care home years, he was visited regularly by a volunteer befriender from his professional body, The Institute of Mechanical Engineers. We will be forever grateful to Roy Pressland, a British Aerospace engineer who listened to Dad’s stories on repeat, brought him industry news and gossip, and helped him reconnect with his professional milestones from Blue Streak to Concorde.

Through ‘tech talk’ with Roy and constant reminiscing with family, Dad’s memories were kept alive as long as humanly possible, giving him handholds in the deep, dark cave of Alzheimer’s. But eventually, heart-breakingly, even his most vivid and cherished memories became unrecoverable.

I am and always will be my father’s daughter, just as we are all and always will be Our Father’s children.

Left: Eley’s dad celebrating his 91st birthday with her younger sister in the ‘pub’ in his care home.

Living in the memories of God

I wish, when that happened, I had read John Swinton’s award-winning Dementia: Living in the Memories of God. Compassionate and clear-eyed about the profound challenges of living with dementia, John challenges the pervasive but flawed linking of human memory and cognition with identity and personhood.

In nearly 300 pages of carefully argued but accessible theology and neurobiology – ‘showing his workings’ in a way dad would certainly approve of – he comes to an uplifting and profoundly hope-filled conclusion:

We may be uncertain who we are, but God is not. God remembers us properly. God remembers us because God knows us…

With all this in mind, it becomes clear that to suggest that God remembers persons with advanced dementia is not a palliative avoidance of the real truth that they have lost their identity. Neither is it an abandonment of these people by God in the present. Quite the opposite. It is a firm statement that God is with and for them and that God is acting with and for them in the present as they move toward God’s future.

pp. 210, 217

There was a moment in The Great Escaper when I knew that, had I been watching with Dad, he would have harrumphed, possibly loudly: a poorly drilled actor gave a badly executed, ‘broken-wristed’ salute. Apart from a brief spell in the Girl Guides, I’ve never had to salute anyone, but I do know that the correct methodology is longest way up, shortest way down, with a straight, flat wrist.

I know this because, even as I come puzzling close to my own three-score years and ten, I am and always will be my father’s daughter, just as we are all and always will be Our Father’s children.

We live now and forever in the memories of God, who promises: ‘I will not forget you! See, I have engraved you on the palms of my hands’ (Isaiah 49:15–16).