Today we remember the Forgotten Army: those who died and those still fighting or imprisoned in the Far East for three torturous months after Victory in Europe was declared on 8 May 1945. We are grateful to Erica Moores, the daughter of a soldier who did return from his imprisonment and forced labour on the ‘Death Railway’, for sharing her father’s story with our communications officer Eley McAinsh.

10 August 2025

Polite but stern

It began with a polite but stern email in response to our March newsletter. Erica wrote:

Hello,

I am grateful for the material about Peace and Reconciliation as we approach the 80th anniversary of VE Day, which, as the name suggests, though an important step in bringing to a close World War II, does not mark the end of the war. As the daughter of a Far East prisoner of war (FEPOW), I and many others feel VJ Day on 15 August, which really did end World War II, is very much the poor relation when it comes to commemorations.

I hope and pray that BRF will mark VJ Day in at least the same way VE Day is being commemorated. The army fighting in Burma after VE Day became known as The Forgotten Army and FEPOWs (and now their children) felt they had been forgotten too. Let’s not forget them now.

Yours in peace,

Erica Moores

Little did I imagine the story to which Erica’s email would lead but now, in advance of the 80th anniversary of VJ Day on Friday, I am honoured to share it.

As the daughter of a Far East prisoner of war, Erica feels VJ Day is very much the poor relation when it comes to commemorations.

A growing campaign

Retired English teacher Erica ‘comes from Manchester and lives in exile in Leeds!’ After studying English and theology at Leeds University, she returned to Manchester, where she got married and had her son. Her husband then got a job back at Leeds University, and Erica spent most of her teaching career in Leeds. They have two children and a grandson who shares his grandma’s passion for drama. Brought up in the Methodist Church, Erica ‘strayed a little and stopped going to church’, before finding her way back, first to the Baptist Church when her son was born and then to the Methodist Church, where she’s ‘been really happy ever since’.

She’s a worship leader and is well known for incorporating drama into services. ‘If I say we’re going to do a Dr Who style nativity play, no one bats an eyelid.’ She’s used New Daylight Bible reading notes for many years and follows all the BRF Ministries news through our emails and newsletters. This is what prompted her email.

‘When I saw the piece about the Burma railway track in the March newsletter, I’d recently found a site on Facebook about the war in the Far East and the children of Far East prisoners of war. As the 80th anniversary of VE Day approached, they were feeling very hurt. Everything was geared towards VE Day in May, but that wasn’t the end of the war in the Far East. That made me determined to be a bit more proactive, and I decided to do whatever I could to make people more aware that the fighting and suffering continued in the Far East after the victory in Europe.’

As a child, Erica remembers her mum telling her how everyone forgot about the Far East after VE Day. ‘She said how very hurtful it was for people who still had loved ones out there. It wasn’t just the prisoners of war, a lot of people were still fighting and the world was not free.’

Two of those ‘forgotten’ prisoners of war were Erica’s dad, Tom, and his long-standing friend and comrade, Percy Blount. Tom survived the horrors of forced labour on the Burma-Thailand railway – the Death Railway – but Percy did not.

Tom had a strong Christian faith, but it was severely tested by his experiences.

Tom and Percy – 1st Battalion, Manchester Regiment

Tom and Percy served together in the 1st Battalion Manchester Regiment, first in Palestine during the so-call Arab Revolt which began in 1936. Then, the year after Japan invaded China in 1937, the regiment was deployed to Singapore, a crucially important British military base and economic port. At first, it seemed an easy posting, as Erica discovered in the archives:

‘They were having football matches, concert parties, all sorts of activities to keep spirits up before the war started. I know my dad broke his nose playing hockey. Everybody thought he did it boxing, so they were a bit afraid of him!’

But then in February 1942 Singapore was captured by the Japanese, resulting in the largest British surrender in history. When Singapore fell Tom and Percy were rounded up, along with the rest of 1st Battalion, and sent first to Changi jail, from where they were sent out on local work parties, and then on to Thailand to work on the Burma–Thailand ‘Death Railway’.

Erica was shocked to discover recently that in May 1942, just a few months after 1st Battalion was captured, Manchester Regiment’s 6th Battalion was renumbered 1st Battalion ‘to replace it’. According to records, ‘the new 1st Battalion remained in Britain until June 1944, when it landed in Normandy. It went on to fight at Caen and Falaise and from there, it fought its way across North-West Europe reaching Hamburg by the war’s end.’

For Erica, it was as if even the army – let alone the public and the politicians – had not just ‘forgotten’ but actively erased all those captured or still fighting in the Far East.

Tom survived the horrors of the Death Railway, but his long-standing friend Percy did not.

The Death Railway

As the current TV dramatisation of Richard Flanagan’s Booker-prize winning novel The Narrow Road to the Deep North shows in unflinching detail, those soldiers’ experiences were brutal beyond imagining.

‘My dad did talk a bit about his experiences,’ says Erica. ‘He told us about the conditions, the privations, the food – I must have been about 18 before he actually ate rice again – and the lengths they had to go to find anything to supplement the meagre rations. He had various illnesses: dysentery, beriberi and malaria, which he continued to have, even when I was a child.’

All the men got sick, and eventually Percy was sent to a hospital inside Burma a week before Tom. It was the first time they’d been apart in all their years serving together. By the time Tom reached the hospital, Percy had died.

Tom had a strong Christian faith, but it was severely tested by his experiences. ‘He was a Christian, but he couldn’t forgive the Japanese,’ says Erica. ‘I think he could have forgiven the Japanese for what had happened to him, but he felt it wasn’t for him to forgive them for what had happened to other people, especially Percy.’

At a desperately low ebb, on the troopship carrying him home from Burma, Tom had a remarkable experience. He only told Erica about it many years later.

‘The thing that had kept him going while he was in Burma was the idea that he’d take his dad for a pint in the pub when he got home. But then he was on the ship on the Red Sea when he got the news that his dad had died and also one of his sisters. So my dad had this double blow, and he was on the deck of the ship on his own late at night and he looked into the water and – I can hear him saying it to me now, it was so vivid the way he told it to me – and he just thought: What’s the point? What was there to go home to? He felt like throwing himself in, but then in that moment of grief he suddenly felt the most remarkable peace come over him. He felt God’s presence so powerfully he knew that he could go on, that God was with him.’

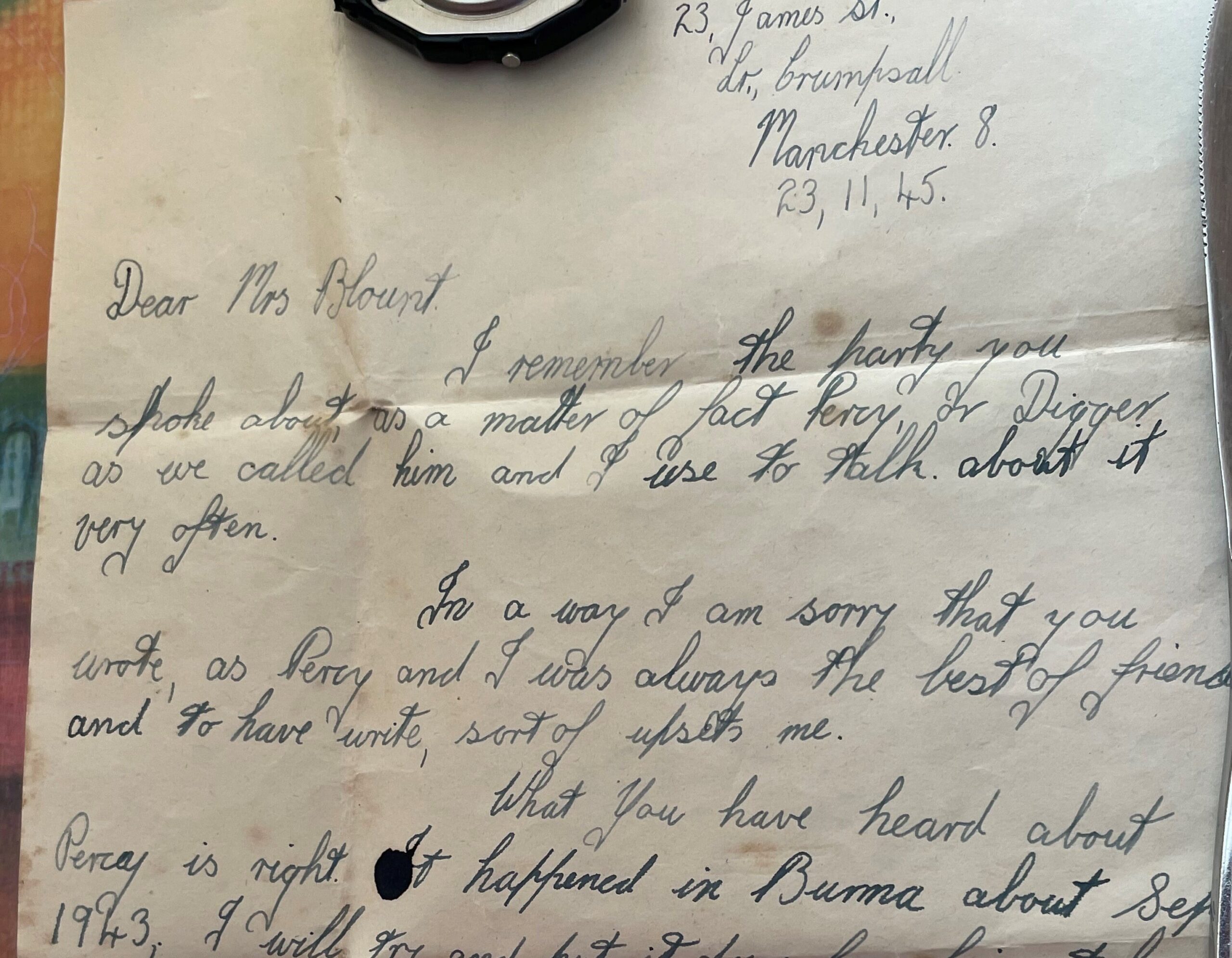

Erica treasures that letter to this day – its polite, restrained tone belying so many heart-breaking experiences.

An unexpected twist

While Tom’s faith helped to sustain him during the brutal years in the Far East, it was Percy’s fiancée Elsie, waiting for him at home, who kept him going until he was finally overwhelmed by hunger and sickness. Because of Percy’s overseas postings, they hadn’t seen each other for ten years when he died.

In a close-knit family and friendship group spanning Manchester and Liverpool, Elsie also knew Tom. Elsie’s sister Doris was married to Percy’s brother, Albert.

‘I don’t know how Doris got my dad’s address,’ says Erica, ‘but somehow she knew where he lived, and she’d remembered him from a birthday party she’d once given for Percy. She wrote to my dad very shortly after he’d returned, and asked him what we could tell her about Percy.’

Tom replied at once and Erica treasures that letter to this day – its polite, restrained tone belying so many heart-breaking experiences. In it he wrote:

‘There is one thing I feel as if I should tell you, as maybe you could tell Elsie better than I. All the while we was abroad and more so when we became prisoners, Percy’s one thought was Elsie. He never could get over the fact that Elsie was waiting for him, some way it seemed to amaze him. He used to say very often: “Fancy Elsie waiting for me. What she sees in me I don’t know.”’

In the letter Tom offered to go to see Doris in Liverpool, and when he told Elsie she said she would go with him to her sister’s to hear all he could tell them about Percy.

In the coming weeks they travelled over to Liverpool several times.

‘From this their relationship grew,’ says Erica, ‘and not long after my dad proposed in this way: “If I asked you to marry me, what would you say?” and Elsie replied, “If you asked me to marry you, I’d say ‘Yes’”. They got married in February 1946, and there’s no doubt they were really in love. They didn’t expect to have children, as doctors had warned dad he might be infertile because of his experiences, but four years later I was born and two years after my brother completed our family.’

Tom and Elsie had a happy marriage, but Tom died at just 61. When Erica was little, he had bouts of malaria and as she grew older her mum told her that he had terrible nightmares for a long time after he came home.

‘My dad used to say the wrong man came back, but I think that was survivor guilt. Of course, there was no support in those days, no understanding of PTSD – my dad would be very understated and just say things like, “I’m kind of sad to talk about it.”’

Tom and Elsie had a happy marriage, but Tom had terrible nightmares for a long time after he came home.

A legacy of hope

Tom trained as a joiner after the war. ‘He was a great dad and a clever man,’ says Erica, ‘but he had difficulty expressing himself. In many ways he was ahead of his time: even though he had little formal education himself, it was dad who encouraged me to go to university and become a teacher.

‘I went to the grammar school but I was a bit of a rebel in my teens. After the third year parents’ evening, my form teacher told me: “You should be really glad you’ve got a dad like that, because he really stuck up for you!”’

When he was 61 Tom became unwell but he continued working, not saying a word to anyone. Only when the pain became too bad for him to work did he finally go to the doctor. He was referred straight to hospital where cancer was diagnosed, and he died just two weeks later, just before his 62nd birthday. ‘It was,’ says Erica, ‘that same resilience he’d shown in the war.’

So, now that she’s shared her father’s story, what does Erica most want people to take away from it?

‘When I first got in touch, I wanted people to see the human face in these events: what VJ Day represents at a very real, human level, even today, 80 years on, not just for the soldiers but for the local people.

‘When I went to Changi Museum in 2014, they told the story of an old lady who, every day when the prisoners were let out of the jail to go and labour on the railway, offered them water. And every day she’d be there with water and every day the Japanese knocked her down. And every day she got up, and the next day she was still there. It was what my dad said: the local people suffered even more than the prisoners of war.

‘So I wanted people to see the bigger picture: a story of human survival, resourcefulness and faith. Yes, the moment dad had on the boat was profound, but I’m sure it was his faith which carried him through the whole experience.’

Changi Museum told the story of an old lady who every day offered the prisoners water.